What Stops the Stock Market Rally?

August, 2020

In terms of magnitude and shortness of time, the stock market rally since its March lows has been unparalleled. Yet it is especially notable given negative economic reality (an annualized second quarter GDP plunge of 32.9%) and diminished company earnings (S&P500 earnings down 50%).1 Will this rally continue? If not, what stops the stock market rally?

Numerous threats exist: continued economic deterioration (a case can be made a recession hit before the lockdowns) and bankruptcies, trade and geopolitical strife with China, civil unrest and mass unemployment, renewed lockdowns due to a Covid resurgence, the loss of hope for a timely vaccine, and a negative economic viewpoint of a very possible Biden presidency.

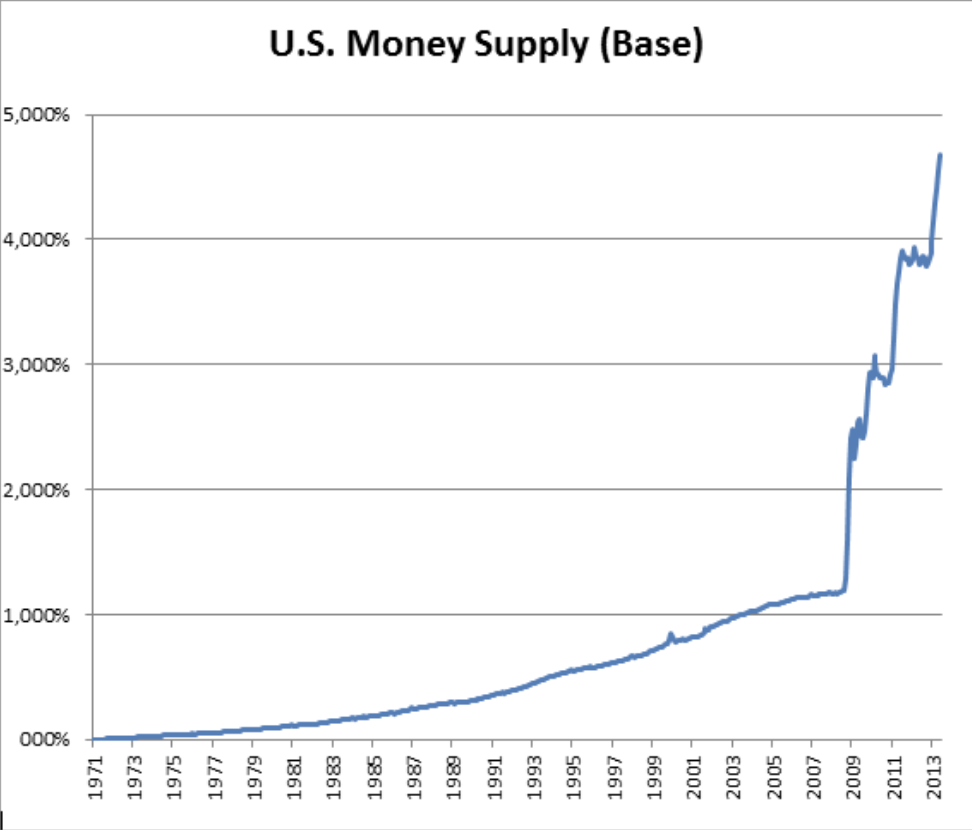

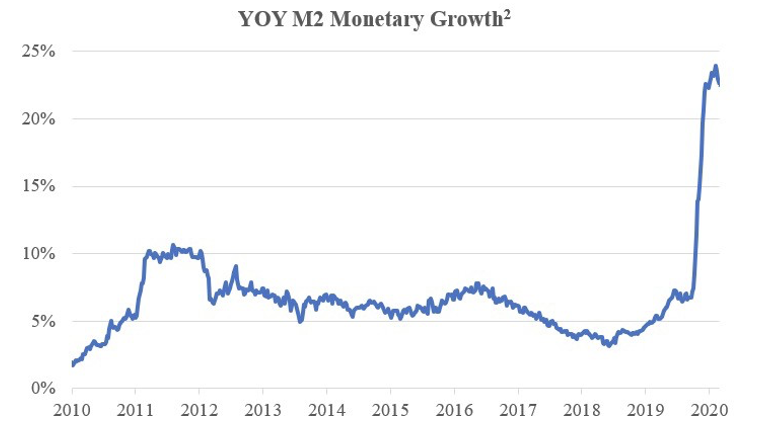

Either mitigating or masking these risks stands the Federal Reserve’s unprecedented actions since March. Although it intervened with numerous programs and purchased a multitude of assets, its actions can be neatly summarized as having massively increased the money supply. Measured in M2 (a commonly cited definition of money) year-over-year growth since the end of the last recession, the money supply has exploded.

Monetary expansion is singularly responsible for the stock market rally. As such, to ask what stops the stock market rally is to question what stops the Federal Reserve.

Chairman Powell is unlikely to voluntarily withdraw monetary stimuli. He learned that lesson (it is no coincidence that the late 2018 stock market decline occurred after a long-term slowdown in monetary growth).

So short of this development, what external factors may prevent the Federal Reserve from pursuing its current monetary course? Theoretically, why is it that central banks cannot forever increasingly print money to ensure ever higher equity prices?

Murray Rothbard, the Austrian school economist and monetary expert, addressed this issue:3

. . . the boom is kept on its way and ahead of its inevitable comeuppance, by repeated doses of the stimulant of bank credit. It is only when the bank credit expansion must finally stop, either because the banks are getting into a shaky condition or because the public begins to balk at the continuing inflation, that retribution finally catches up with the boom. As soon as the credit expansion stops, then the piper must be paid . . .

The “shaky condition” of banks may derive from low absolute interest rate spreads and unsustainable financial leverage alongside increasing bad loans. It will develop with sustained negative real rates (as it has in other parts of the world).

Assuming a banking crisis is averted, what about inflation? Few under 50-years old can remember, let alone experienced, an inflationary environment as a consumer, but could one be starting now? According to the August 14th issue of Barron’s magazine:4

A trifecta of inflation numbers came in hotter than expected this past week, with consumer prices, producer prices, and import prices for July all rising at faster paces than economists anticipated. Notably, consumer prices – excluding the more volatile food and energy categories – rose at the quickest clip since 1991.

It may not be starting now, but it could be. And unlike the 1970’s, the Federal Reserve will be unable to deflect blame at greedy business owners or higher oil prices. What they once could play off as coincidence will now reek of causality. And if they stop inflating, then any rally could turn to rout.

Endnotes:

- S&P500 Down Jones (95% of companies reporting)

- Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

- Rothbard, Murray N. Economic Depressions: Their Cause & Cure. Ludwig von Mises Institute. 2009.

- ‘Stagflation’ Looms Over This Market. Why Some Analysts are Worried. Bellfuss, Lisa. Barron’s. 14 August 2020