Echoes of 1974

Each year brings investors a fresh list of hopes and fears. Often, mainstream financial firms provide guidance that extrapolates linear thinking into the future. We prefer to take a more cyclical view of the world to glean knowledge from patterns in past cycles that rhyme with today. With that in mind, we set our sights back 50 years ago to 1974, just long enough for most investors to have forgotten those events, and the lessons associated with them. There are five key lessons from that period that we believe are relevant to investors today.

Lesson 1: Inflation & Interest Rates – Volatile But Trending Upward

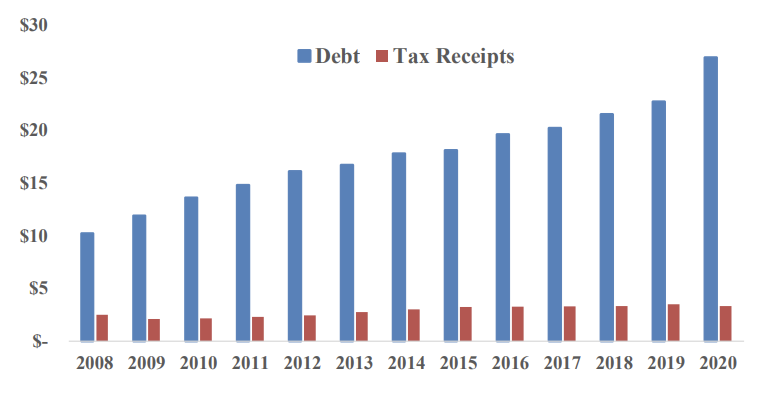

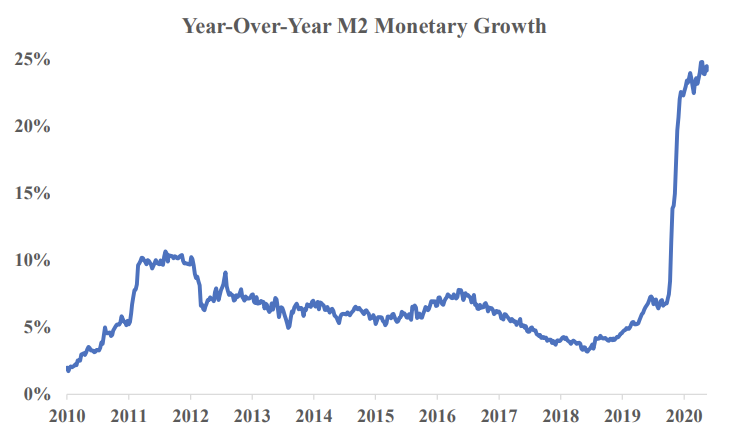

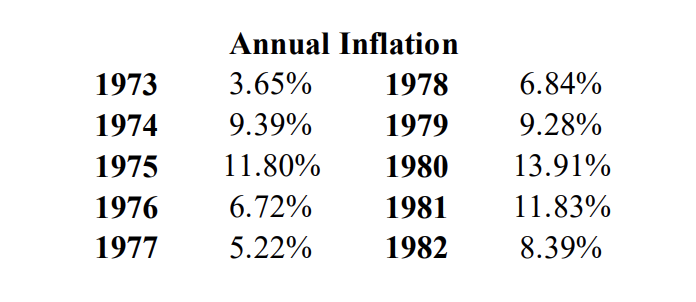

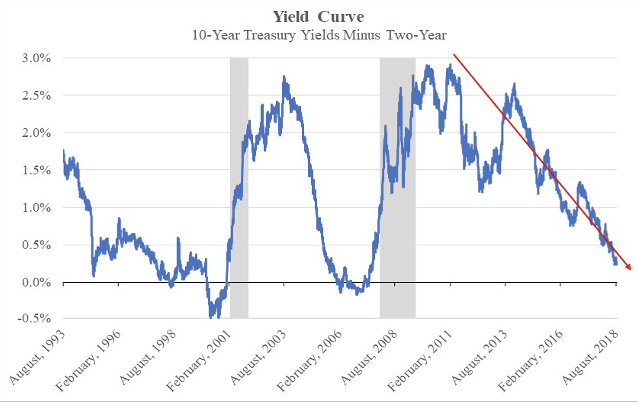

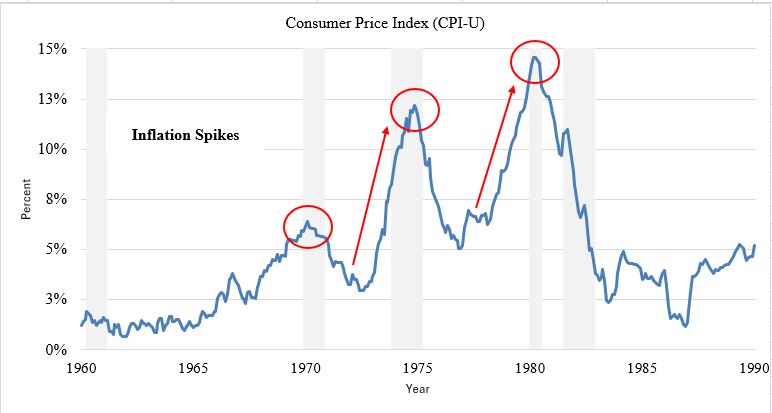

After experiencing renewed inflation in the early 1970’s, 1974 was an inflection point that marked a relative high in annual inflation of 11.1% and interest rates 10.5% (short-term T-bills) and 7.6% (10-year Treasuries). A significant recession hit in 1974 and inflation and interest rates fell. Like today, the consensus was that rising inflation and rising rates were a “blip on the radar” with the worst likely behind us. However, inflation and interest rates aggressively reasserted themselves several years later in a second major upcycle in the late 1970s. Inflation soared to 13.5% at its 1980 peak, pushing interest rates to 16.4% (short-term T-bills) and 13.9% (10-year Treasuries) by 1981.

1

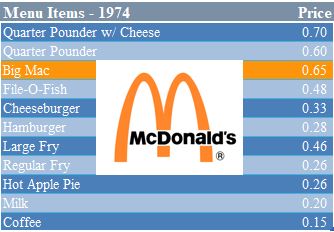

Despite the inflation at the time, a Big Mac at McDonalds was only 65 cents, and it was actually called “Big” for a reason!

2

The Lesson Today:

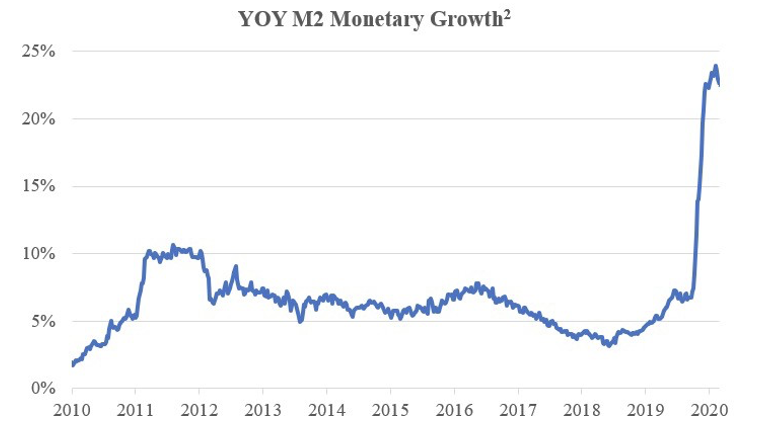

While inflation fell leading into 2024 and 10-year Treasuries remain around 4%, inflation is not dead. It is wise to prepare for a second, bigger wave of rising inflation and interest rates in the coming decade. That said, 2024 may bring a continued temporary lull in inflation and interest rates if global economies weaken. The big caveat for this “lull scenario” is the massive Federal debt levels relative to 1974. The official national debt has surpassed $34 trillion and added a whopping $1 trillion in the last 30 days alone! The question is not who will buy the debt, as there will always be takers at the right price. The question is what interest rate will be demanded by investors.

Lesson 2: Extreme Stock Valuation Led to Pain

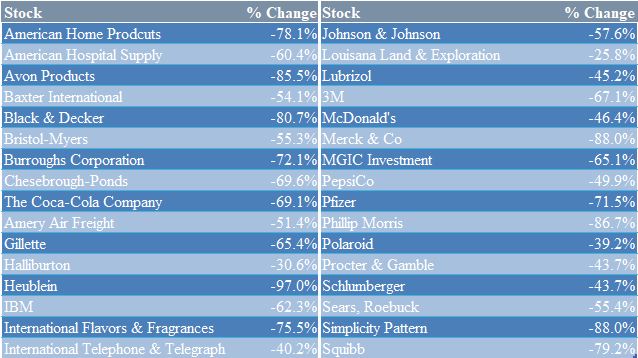

Today’s Magnificent 7 tech stocks have led the S&P500 with extremely narrow stock market leadership.3 Their valuations continue to rival periods such as the 2000 Tech Bubble and the Nifty Fifty from 1974 (a basket of 50 stocks that people believed would lead to outsized returns with a single buy-and-hold proposition). These stocks were the leaders of that era until their ultimate crash into the recession of 1974 when most lost 50% to 80% of their value.

4

The Lesson Today:

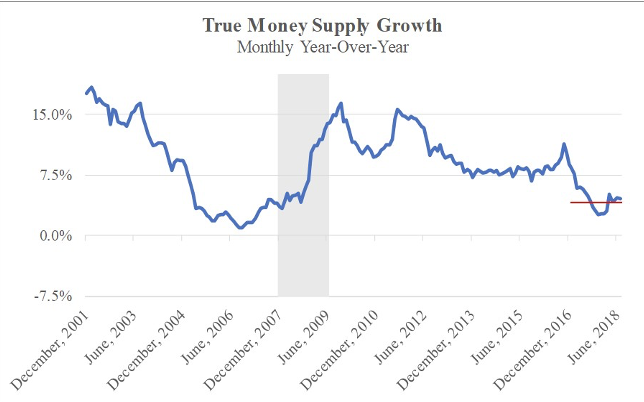

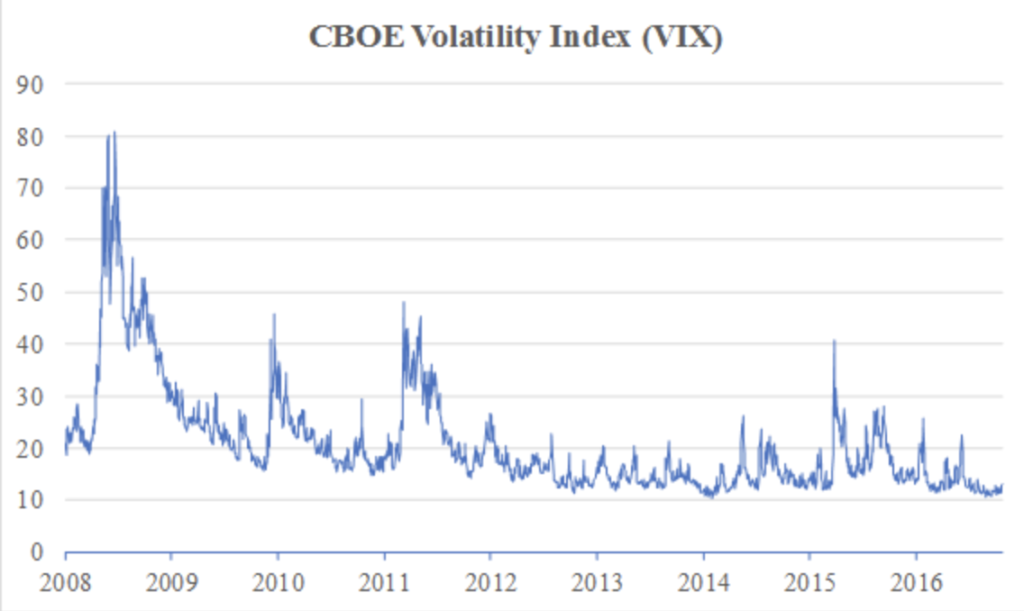

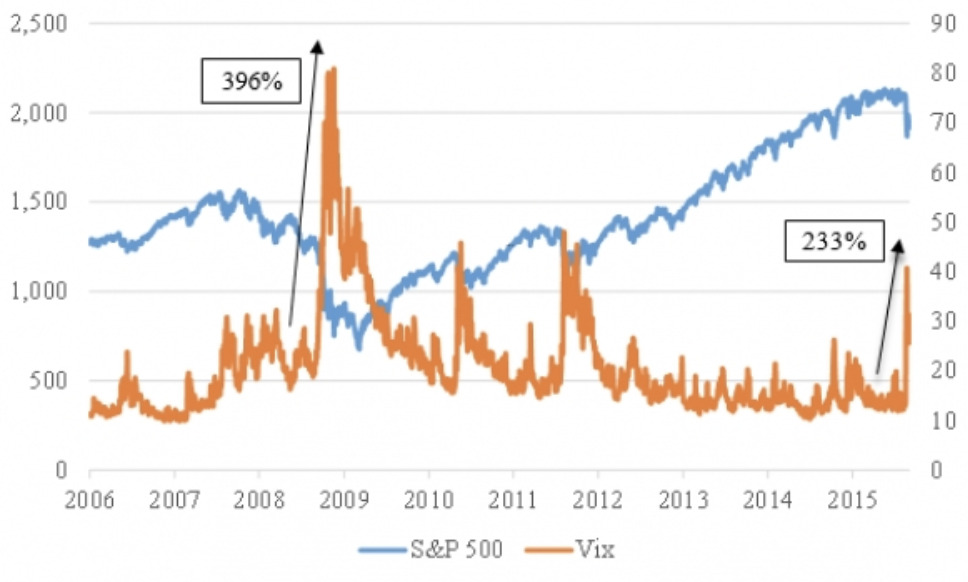

When investors fall in love with a narrow group of expensive stocks that have pushed up the stock indices, markets are at risk to greatly disappoint (or crash). Today, the S&P500 has been mainly driven by just seven stocks or approximately 1.4% of total stocks in the index. This suggests the near-term prospects for equities are challenged barring any surprise return to money printing. Although money printing will return, it will take significant pain in the stock markets first for the Fed to justify it.

Lesson 3: Political Instability Rising

President Nixon was the first president to “voluntarily” resign in 1974 amidst the Watergate scandal. This led to an era of distrust and loss of confidence in the government and economy for nearly a decade. Today, the political environment is rife with instability as we enter an election year with a divided country, polarized views, and questions at every level of government.

The Lesson Today:

Politics is a key factor in the confidence of a healthy, functioning capitalistic system. When markets feel at risk and do not trust the institutions or the rules, faith can be lost and not easily recovered.

Lesson 4: War, Energy & the Middle East

The Yom Kippur War between Israel and several Arab nations in the fall of 1973 led to an oil embargo and spike in energy prices. Eerily, another conflict in the Middle East began last year one day removed from the 50th anniversary of this war, sparking many unknown, long-term consequences.

The Lesson Today:

War in the Middle East has many geopolitical implications. It risks dividing countries and causing an unknown future impact on energy markets. Global war, if this were to expand, often goes hand in hand with difficult economic times in history. War has always been a great excuse to tear things up and rebuild them, but not always to benefit of the average citizen.

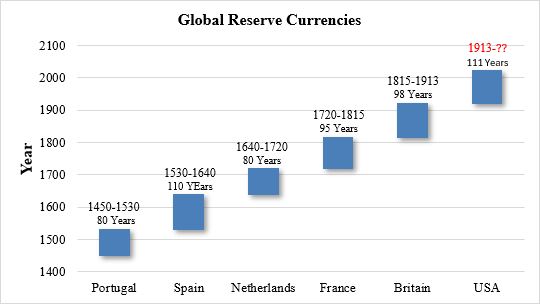

Lesson 5: Changing of the Guard in Currencies Every 100 Years

The early 1970s was a critical time for the U.S. dollar. What had been a pre-World War II system of currencies disciplined by the backing of physical gold or silver morphed into a dollar system under the Bretton Woods Agreement. However, holders of dollars became increasingly nervous in the early 1970s as U.S. spending was seemingly out of control (imagine if they could see things today!) due to social programs and the Vietnam War. The Bretton Woods system promised the dollar could be converted to gold – until it couldn’t. France led the charge to redeem dollars for gold. This resulted in President Nixon’s famous 1971 speech in which he was “temporarily suspending the convertibility of the dollar to gold”. Of course, like most things from the government, temporary programs never go away. From that point forward, the dollar was simply printed out of thin air without constraints.

Today, we are nearing another critical event in the life of the dollar – a rise in nations circumventing the dollar system as seen in the growing alliance of BRICS countries expanding non-dollar denominated trade.5

6

The Lesson Today:

No reserve currency has lasted more than approximately 100 years. Given this, the dollar is late in its life cycle as measured from the 1913 inception of the Federal Reserve system. While the dollar is not on its immediate way out, we envision world trade and capital markets becoming more multi-polar as reliance on the dollar fades. Eventually, the reality must be faced that the U.S. national debt cannot be serviced without creating a death spiral of more money printed just to service debt. Other world currencies face a similar predicament with no likely predecessor. Thus, the world will likely start a gradual, and then sudden path back to sound money (likely precious metals and perhaps cryptocurrencies) – not by choice, but by necessity.

Endnotes:

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US). “10-Year Treasury Constant Maturity Rate.” FRED,

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 2 Jan. 1962, fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DGS10/. - “Vintage McDonald’s Menu from the 70s Reveals How Much Has Changed over the Last 40 Years.” Throwbacks,

31 Aug. 2023, throwbacks.com/vintage-mcdonalds-menu-from-the-70s-reveals-how-much-has-changed-over-thelast-

40-years/. - Magnificent 7 stocks: Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia, Tesla

- “Revisiting the Nifty Fifty.” Stray Reflections – Revisiting the Nifty Fifty, strayreflections.

com/article/252/Revisiting_the_Nifty_Fifty. - BRICS: Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa

- “World Reserve Currencies: What Happened during Previous Periods of Transition? Economic Reason.”

www.economicreason.com/usdollarcollapse/world-reserve-currencies-what-happened-during-previous-periods-oftransition/.