Inflation Fears: Shades of 1974?

Echoes of 1974

Each year brings investors a fresh list of hopes and fears. Often, mainstream financial firms provide guidance that extrapolates linear thinking into the future. We prefer to take a more cyclical view of the world to glean knowledge from patterns in past cycles that rhyme with today. With that in mind, we set our sights back 50 years ago to 1974, just long enough for most investors to have forgotten those events, and the lessons associated with them. There are five key lessons from that period that we believe are relevant to investors today.

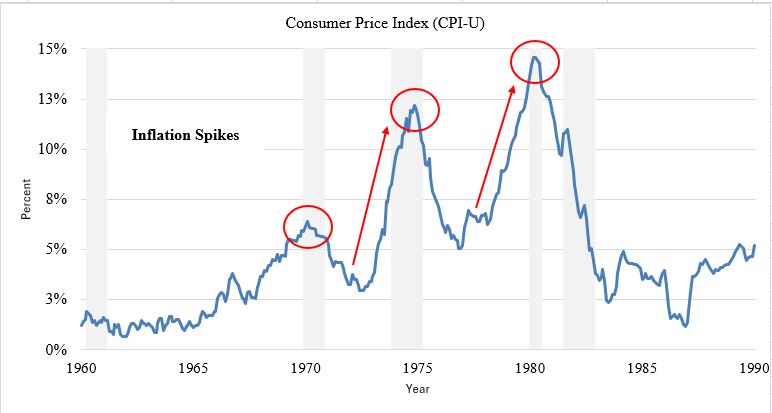

Lesson 1: Inflation & Interest Rates – Volatile But Trending Upward

After experiencing renewed inflation in the early 1970’s, 1974 was an inflection point that marked a relative high in annual inflation of 11.1% and interest rates 10.5% (short-term T-bills) and 7.6% (10-year Treasuries). A significant recession hit in 1974 and inflation and interest rates fell. Like today, the consensus was that rising inflation and rising rates were a “blip on the radar” with the worst likely behind us. However, inflation and interest rates aggressively reasserted themselves several years later in a second major upcycle in the late 1970s. Inflation soared to 13.5% at its 1980 peak, pushing interest rates to 16.4% (short-term T-bills) and 13.9% (10-year Treasuries) by 1981.

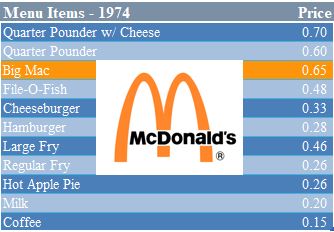

1

Despite the inflation at the time, a Big Mac at McDonalds was only 65 cents, and it was actually called “Big” for a reason!

2

The Lesson Today:

While inflation fell leading into 2024 and 10-year Treasuries remain around 4%, inflation is not dead. It is wise to prepare for a second, bigger wave of rising inflation and interest rates in the coming decade. That said, 2024 may bring a continued temporary lull in inflation and interest rates if global economies weaken. The big caveat for this “lull scenario” is the massive Federal debt levels relative to 1974. The official national debt has surpassed $34 trillion and added a whopping $1 trillion in the last 30 days alone! The question is not who will buy the debt, as there will always be takers at the right price. The question is what interest rate will be demanded by investors.

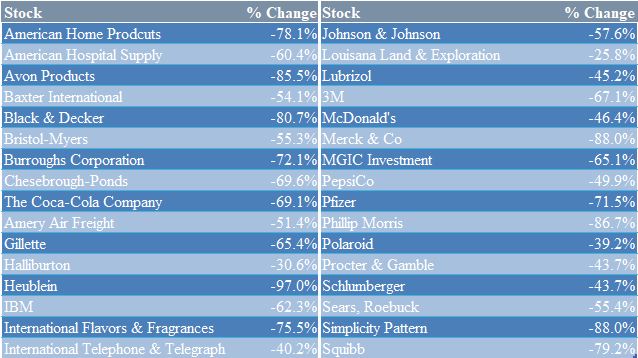

Lesson 2: Extreme Stock Valuation Led to Pain

Today’s Magnificent 7 tech stocks have led the S&P500 with extremely narrow stock market leadership.3 Their valuations continue to rival periods such as the 2000 Tech Bubble and the Nifty Fifty from 1974 (a basket of 50 stocks that people believed would lead to outsized returns with a single buy-and-hold proposition). These stocks were the leaders of that era until their ultimate crash into the recession of 1974 when most lost 50% to 80% of their value.

4

The Lesson Today:

When investors fall in love with a narrow group of expensive stocks that have pushed up the stock indices, markets are at risk to greatly disappoint (or crash). Today, the S&P500 has been mainly driven by just seven stocks or approximately 1.4% of total stocks in the index. This suggests the near-term prospects for equities are challenged barring any surprise return to money printing. Although money printing will return, it will take significant pain in the stock markets first for the Fed to justify it.

Lesson 3: Political Instability Rising

President Nixon was the first president to “voluntarily” resign in 1974 amidst the Watergate scandal. This led to an era of distrust and loss of confidence in the government and economy for nearly a decade. Today, the political environment is rife with instability as we enter an election year with a divided country, polarized views, and questions at every level of government.

The Lesson Today:

Politics is a key factor in the confidence of a healthy, functioning capitalistic system. When markets feel at risk and do not trust the institutions or the rules, faith can be lost and not easily recovered.

Lesson 4: War, Energy & the Middle East

The Yom Kippur War between Israel and several Arab nations in the fall of 1973 led to an oil embargo and spike in energy prices. Eerily, another conflict in the Middle East began last year one day removed from the 50th anniversary of this war, sparking many unknown, long-term consequences.

The Lesson Today:

War in the Middle East has many geopolitical implications. It risks dividing countries and causing an unknown future impact on energy markets. Global war, if this were to expand, often goes hand in hand with difficult economic times in history. War has always been a great excuse to tear things up and rebuild them, but not always to benefit of the average citizen.

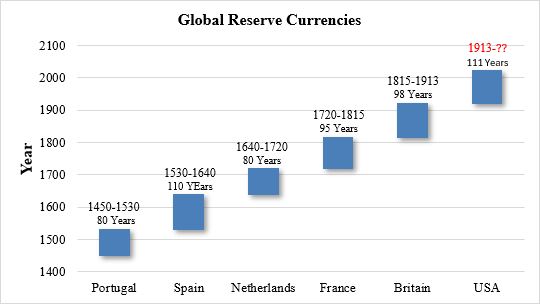

Lesson 5: Changing of the Guard in Currencies Every 100 Years

The early 1970s was a critical time for the U.S. dollar. What had been a pre-World War II system of currencies disciplined by the backing of physical gold or silver morphed into a dollar system under the Bretton Woods Agreement. However, holders of dollars became increasingly nervous in the early 1970s as U.S. spending was seemingly out of control (imagine if they could see things today!) due to social programs and the Vietnam War. The Bretton Woods system promised the dollar could be converted to gold – until it couldn’t. France led the charge to redeem dollars for gold. This resulted in President Nixon’s famous 1971 speech in which he was “temporarily suspending the convertibility of the dollar to gold”. Of course, like most things from the government, temporary programs never go away. From that point forward, the dollar was simply printed out of thin air without constraints.

Today, we are nearing another critical event in the life of the dollar – a rise in nations circumventing the dollar system as seen in the growing alliance of BRICS countries expanding non-dollar denominated trade.5

6

The Lesson Today:

No reserve currency has lasted more than approximately 100 years. Given this, the dollar is late in its life cycle as measured from the 1913 inception of the Federal Reserve system. While the dollar is not on its immediate way out, we envision world trade and capital markets becoming more multi-polar as reliance on the dollar fades. Eventually, the reality must be faced that the U.S. national debt cannot be serviced without creating a death spiral of more money printed just to service debt. Other world currencies face a similar predicament with no likely predecessor. Thus, the world will likely start a gradual, and then sudden path back to sound money (likely precious metals and perhaps cryptocurrencies) – not by choice, but by necessity.

Endnotes:

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US). “10-Year Treasury Constant Maturity Rate.” FRED,

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 2 Jan. 1962, fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DGS10/. - “Vintage McDonald’s Menu from the 70s Reveals How Much Has Changed over the Last 40 Years.” Throwbacks,

31 Aug. 2023, throwbacks.com/vintage-mcdonalds-menu-from-the-70s-reveals-how-much-has-changed-over-thelast-

40-years/. - Magnificent 7 stocks: Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia, Tesla

- “Revisiting the Nifty Fifty.” Stray Reflections – Revisiting the Nifty Fifty, strayreflections.

com/article/252/Revisiting_the_Nifty_Fifty. - BRICS: Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa

- “World Reserve Currencies: What Happened during Previous Periods of Transition? Economic Reason.”

www.economicreason.com/usdollarcollapse/world-reserve-currencies-what-happened-during-previous-periods-oftransition/.

Fractional Reserve Airline Seats

This article was originally published by The Ludwig von Mises Institute of Canada on April 18, 2017

Every year, airlines deny thousands of passengers seats on flights due to overbooking. Airlines use sophisticated modeling to manage overbooking to maximize profits given the reality of passenger no- shows. Legally permissible under their “contract of carriage” with passengers, fewer than one-tenth of one percent of all passengers lose seats due to overbooking. 1 But when Dr. David Dao was violently removed from a United Airlines flight in Chicago, it did far more than generate a public relations nightmare; it exposed the absurdity of fractional reserve banking.

If an airline had 100 seats and overbooked by 10, then 91% of their seats are “reserved”. U.S. banks need only retain an effective 10% of demand deposits on hand for withdrawals while Canadian banks have no reserve requirement. Baring general capital requirements, the remainder can and is typically lent to borrowers. If an airline used 10% fractional reserve seating, the number of stranded passengers would approach 900 for a 100-seat airplane. The refugee-like look of an airline gate under such a situation would be no different than the typical bank run during the Great Depression.

Unfortunately, just as passengers lack legal recourse when denied seats, demand depositors cannot seek redress when their withdrawals are refused. As Murray Rothbard detailed in The Case Against the Fed and his other books on the history of banking, it was unfortunate 19th-century case law ceased recognizing a deposit as a bailment (the custody of another’s possessions). As Rothbard opined, the legal cover given fractional reserve banking cannot mask the fraudulent nature of lending against demand deposits. And no “contract” between a depositor and a bank can legitimize fractional reserve banking, just as naming something a “square circle” cannot create such a shape.

Even people versed in Austrian economics fail to understand the nature of fractional reserve banking. In an August 17, 2014 Forbes article entitled The Closing of the Austrian School’s Economic Mind, columnist John Tamny wrote:

“This alleged “multiplication” of money all sounds so frightening at first glance, but for those who think there might be some truth to the “money multiplier,” DO try it at home among friends. Hand the first friend $1,000, and let him lend $900 to the person next to him, followed by an $810 loan to the next tablemate. What those who try it will find is that far from creating $2,710 worth of access to the economy’s resources, there will still be only $1,000; the original holder of $1,000 with $100 in his possession, $90 in the second person’s hands, followed by $810 in the third.”2

And yet this illustration proves the opposite of Tamny’s conclusion, for the money supply is not just the physical dollars on the table. If the arrangements between the participants allow for withdrawals on demand, then each person would assume their cash balances equaled their cash on hand as well as their “demand deposit” with the next person. The money supply would absolutely equal $2,710 with only $1,000 in physical currency.

Although few understand fractional reserve banking, even fewer appreciate its repercussion. So while Dr. Dao could passively resist fractional reserve airline seats, none of us can escape the business cycles and price inflation caused by fractional reserve banking.

About the Author: Christopher P. Casey, CFA®, is a Managing Director with WindRock Wealth Management. Mr. Casey advises clients on their investment portfolios in today’s world of significant economic and financial intervention. He can be reached at 312-650-9602 or chris.casey@windrockwealth.com.

WindRock Wealth Management is an independent investment management firm founded on the belief that investment success in today’s increasingly uncertain world requires a focus on the macroeconomic “big picture” combined with an entrepreneurial mindset to seize on unique investment opportunities. We serve as the trusted voice to a select group of high net worth individuals, family offices, foundations and retirement plans.

All content and matters discussed are for information purposes only. Opinions expressed are solely those of WindRock Wealth Management LLC and our staff. Material presented is believed to be from reliable sources; however, we make no representations as to its accuracy or completeness. All information and ideas should be discussed in detail with your individual adviser prior to implementation. Fee-based investment advisory services are offered by WindRock Wealth Management LLC, an SEC-Registered Investment Advisor. The presence of the information contained herein shall in no way be construed or interpreted as a solicitation to sell or offer to sell investment advisory services except, where applicable, in states where we are registered or where an exemption or exclusion from such registration exists. WindRock Wealth Management may have a material interest in some or all of the investment topics discussed. Nothing should be interpreted to state or imply that past results are an indication of future performance. There are no warranties, expresses or implied, as to accuracy, completeness or results obtained from any information contained herein. You may not modify this content for any other purposes without express written consent.

Endnotes:

1Ben-Achour, Sabri. “Why in the world do airlines overbook tickets?” Marketplace. 27 April 2015. https://www.marketplace.org/2015/04/27/business/ive- always-wondered/why-world-do-airlines-overbook-tickets.

2 Tamny, Joh. “The Closing of the Austrian School’s Economic Mind” Forbes. 17 August 2014. https://www.forbes.com/sites/johntamny/2014/08/17/the- closing-of-the-austrian-schools-economic- mind/#36b63f455147

Velocity Lacks Veracity

Christopher P. Casey

Typically defined as “the number of times one dollar is spent to buy goods and services per unit of time,” historically low monetary velocity is blamed for stymieing the Federal Reserve’s ability to achieve a targeted rate of price inflation.1 It is cited as delaying the onset of price inflation which was imminently predicted by some financial commentators in the aftermath of the Great Recession. It is viewed by all as problematic as it is powerful, as vexing as it is valid. Yet, despite its nature and magnitude having been debated for decades between Keynesian and Monetarist economists, monetary velocity is simply a pervasive and damaging myth.

The concept of velocity derives from the Fisher Equation of Exchange: MV=PT, where the quantity of money (M) times the velocity of its circulation (V) equals prices (P) multiplied by their related transactions(T). Initially developed by Copernicus, its modern manifestation was promulgated by the economist Irving Fisher in 1911.2 3 The equation attempts to explain increases (or decreases) in the price level: if the quantity of money expands, then prices will rise unless velocity decreases (or if transactions increase).

Valid criticisms of velocity are numerous: that the equation is merely tautological (it should be self-evident that prices paid for goods and services equal the prices charged for such goods and services), that the velocity of money cannot exist apart from the circulation of goods and services, that velocity is an effect and not a cause of price movements, etc. All of these arguments, while completely correct, avoid the primary reason velocity confuses mainstream economic prophets and financial prognosticators alike, for any theory of prices cannot ignore the demand for money. Murray Rothbard recognized this as the Fisher Equation’s fatal flaw: “it is this profound mistake that lies at the root of the fallacies of the Fisher equation of exchange: human action is abstracted out of the picture.”4 The abstraction of human action means the absence of monetary demand.

Why the Fisher Equation is Wrong

Without the foundation of the Fisher Equation, velocity loses any theoretical justification. Historical examples of price inflation failing to correspond with the mechanistic workings of the Fisher Equation demonstrate the equation’s falsehood. In the “Velocity of Circulation” (from Money, the Market, and the State), Henry Hazlitt shattered the Fisher Equation and underscored the importance of monetary demand by describing the historical behavior of price inflation:

What we commonly find, in going through the histories of substantial or prolonged inflations in various countries, is that, in the early stages, prices rise by less than the middle stages they may rise in rough proportion to the increase in the quantity of money . . . but that, when an inflation has been prolonged beyond a certain point, or has shown signs of acceleration, prices rise by more than the increase in the quantity of money.5

In losing the formulaic correlation of the Fisher Equation, velocity drops all claims to causation. But not only does the Fisher Equation fail to comport with historical fact patterns, it also rejects basic economic theory. Almost all economists today recognize that the price for any particular good or service derives from the interaction of supply and demand. The Austrian economists, since the 1912 publication of Ludwig von Mises’ Theory of Money and Credit, have applied this logical and consistent principle to the concept of money:

The changes in the purchasing power of the monetary unit are brought about by changes arising in the relation between the demand for money, i.e., the demand for money for cash holding, and the supply of money.6

The “price” of money derives from the same supply and demand dynamic as any good or service. In excluding monetary demand, the Fisher Equation loses all explanatory authority. And velocity cannot purport to act as a proxy for monetary demand.

Why Velocity is Not Monetary Demand

Velocity is not a substitute for demand, but rather of volume. Lots of goods and services may transact at low prices just as they may trade at high prices. In either scenario, “velocity” is high while the demand for money may be low or high. The situation is analogous to daily price changes in the stock market: equity indices may fall or rise significantly (largely a function of demand as the supply of shares is fairly consistent from day to day) with large or little trading volume. In either scenario, price levels are invariant to volume. As such, velocity lends no insight or description of demand for any good or service – or money.

What is the demand for money, and what influences it? The demand for money is the desire for particular levels of cash holdings. In Man, Economy, and State, Rothbard detailed monetary demand’s constituent parts as the exchange demand for money (the degree to which holders of goods and services wish to trade for money) and the reservation demand for money (the degree to which current holders of money wish to keep it). Regardless, the desire for cash holdings depends upon an ever-changing determination of values and preferences by economic actors. It is certainly influenced by future uncertainty, expectations as to future purchases, and anticipated future price levels. The criteria influencing monetary demand are as myriad and complex as the nature of the various economic actors desiring cash holdings.

Conclusion

In divorcing monetary demand from the determination of purchasing power, the Fisher Equation detaches price level analysis from reality. Rothbard recognized its negative potential when he described it as “at best . . . superfluous and trivial, at worst . . . wrong and misleading.” The latter situation exists with the Federal Reserve’s false focus on monetary velocity as an impediment to their stated price inflation targets. To overcome this bogus barrier, the Federal Reserve will continue to increase the money supply. When significant price inflation develops, the realization of this mistake, if they realize it at all, will be too late.

Endnotes:

- St. Louis Federal Reserve.

- Rothbard, Murray. Economic Thought Before Adam Smith (Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd., 1995).

- Fisher, Irving. The Purchasing Power of Money (New York: Macmillan, 1911).

- Rothbard, Murray. Man, Economy, and State (William Volker Fund, 1962).

- Hazlitt, Henry. “Velocity of Circulation” from Money, the Market, and the State, (Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 1968).

- von Mises, Ludwig. Theory of Money and Credit (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1953).

About WindRock

WindRock Wealth Management is an independent investment management firm founded on the belief that investment success in today’s increasingly uncertain world requires a focus on the macroeconomic “big picture” combined with an entrepreneurial mindset to seize on unique investment opportunities. We serve as the trusted voice to a select group of high-net-worth individuals, family offices, foundations and retirement plans.

312-650-9822

Bitcoin or Gold?

This article was originally published by The Human Events Group on July 3, 2014

We have proposed a system for electronic transactions without relying on trust. – Satoshi Nakamoto, 20091

With this fairly mundane comment, the person or persons known as Satoshi Nakamoto (the jury is still be out) introduced bitcoin to the world. Since then, bitcoin has attracted widespread attention and interest – as well as numerous critics. Ironically, some of its most vocal detractors, such as Austrian economist Frank Shostak and financial commentator Peter Schiff, are champions of gold. As fiat currencies (money which exists solely due to the force of law, i.e., by fiat) further decline in value, will investors increasingly embrace a cryptocurrency such as bitcoin, or will they revert to the historically tried-and-true precious metals? Will it be bitcoin or gold?

As the values of bitcoin and gold are primarily contingent on their future acceptance as money, answering the question “bitcoin or gold” requires an examination of a more basic inquiry: what is money? Money is a medium of exchange and, as such, presupposes the ability to act as a store of value. Over two thousand years ago, Aristotle noted the primary qualities exhibited by money:

- Portability

- Durability

- Homogeneity, and

- Divisibility.

Money should also, at least before becoming accepted as money, possess “alternative value.” This term is unfortunately sometimes referred to as “intrinsic” value (as nothing possesses value without demand, nothing is intrinsically valuable).2 Gold, (and to a lesser extent silver) possesses these qualities and was therefore used as money until quite recently (1971). Bitcoin critics who are proponents of gold cite its lack of alternative value as a fatal flaw.

But is it? True, unlike gold or silver, bitcoin cannot be used for a non-monetary purpose. Perhaps this is not a weakness, but rather a strength. As bitcoin lacks physical form, it lacks alternative value, but herein lies its unique attribute relative to gold – there is nothing to physically transmit. In the characteristic of portability, it easily exceeds gold’s virtues.

Does this mean that bitcoin is no different than any fiat money which can be transferred with a computer keystroke? No, as its usage derives from general acceptance, not mandate.

And unlike the experience of all fiat currencies throughout time, bitcoin is limited in quantity (it is designed so only 21 million bitcoins can ever be “mined” into existence). Nakamoto remarked that in creating bitcoin he had removed trust. But more accurately, he removed faith and fortified trust, for just as gold and silver use nature (their elemental physical characteristics) as an objective standard, so bitcoin utilizes math (cryptography).

The question of what ultimately may be the future of money may be “bitcoin or gold?”, but perhaps the answer should be bitcoin and gold. For millennia, gold and silver coexisted as money, so why not bitcoin as well? Bitcoin is so unique in the history of money, and so complementary to gold, that one day in the future, it – or some other cryptocurrency (assuming they survive government regulation and financial repression) – may become more than today’s speculative investment.

Endnotes:

1 Nakamoto, Satoshi. Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System. 24 May 2009 <http://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf>.

2 For a real life example of the importance of “alternative value” as a quality of money, see “Only Criminals Use Honest Money” by Christopher Casey as published by the Mises Institute. <https://mises.org/library/only-criminals-use- honest-money>.

About the Author: Christopher P. Casey is a Managing Director with WindRock Wealth Management. Mr. Casey advises clients on their investment portfolios in today’s world of significant economic and financial intervention. He can be reached at 312-650- 9602 or chris.casey@windrockwealth.com.

WindRock Wealth Management is an independent investment management firm founded on the belief that investment success in today’s increasingly uncertain world requires a focus on the macroeconomic “big picture” combined with an entrepreneurial mindset to seize on unique investment opportunities. We serve as the trusted voice to a select group of high net worth individuals, family offices, foundations and retirement plans.

All content and matters discussed are for information purposes only. Opinions expressed are solely those of WindRock Wealth Management LLC and our staff. Material presented is believed to be from reliable sources; however, we make no representations as to its accuracy or completeness. All information and ideas should be discussed in detail with your individual adviser prior to implementation. Fee-based investment advisory services are offered by WindRock Wealth Management LLC, an SEC-Registered Investment Advisor. The presence of the information contained herein shall in no way be construed or interpreted as a solicitation to sell or offer to sell investment advisory services except, where applicable, in states where we are registered or where an exemption or exclusion from such registration exists. WindRock Wealth Management may have a material interest in some or all of the investment topics discussed. Nothing should be interpreted to state or imply that past results are an indication of future performance. There are no warranties, expresses or implied, as to accuracy, completeness or results obtained from any information contained herein. You may not modify this content for any other purposes without express written consent.

Deflating the Deflation Myth

Mises.org

Publish Date: April 2, 2014 – 12:00 AM

Author 1: Christopher P. Casey [1]

The fear of deflation serves as the theoretical justification of every inflationary action taken by the Federal Reserve and central banks around the world. It is why the Federal Reserve targets a price inflation rate of 2 percent, and not 0 percent. It is in large part why the Federal Reserve has more than quadrupled the money supply since August 2008. And it is, remarkably, a great myth, for there is nothing inherently dangerous or damaging about deflation.

Deflation is feared not only by the followers of Milton Friedman (those from the so-called Monetarist or Chicago School of economics), but by Keynesian economists as well. Leading Keynesian Paul Krugman, in a 2010 New York Times article titled “Why Deflation is Bad,” cited deflation as the cause of falling aggregate demand since “when people expect falling prices, they become less willing to spend, and in particular less willing to borrow.”1

Presumably, he believes this delay in spending lasts in perpetuity. But we know from experience that, even in the face of falling prices, individuals and businesses will still, at some point, purchase the good or service in question. Consumption cannot be forever forgone. We see this every day in the computer/electronics industry: the value of using an iPhone over the next six months is worth more than the savings in delaying its purchase.

Another common argument in the defamation of deflation concerns profits. With falling prices, how can businesses earn any as profit margins are squeezed? But profit margins by definition result from both sale prices and costs. If costs — which are after all prices themselves — also fall by the same magnitude (and there is no reason why they would not), profits are unaffected.

If deflation impacts neither aggregate demand nor profits, how does it cause recessions? It does not. Examining any recessionary period subsequent to the Great Depression would lead one to this conclusion.

In addition, the American economic experience during the nineteenth century is even more telling. Twice, while experiencing sustained and significant economic growth, the American economy “endured”

deflationary periods of 50 percent.2 But what of the “statistical proof” offered in Friedman’s A Monetary History

of the United States? A more robust study has been completed by several Federal Reserve economists who found:

… the only episode in which we find evidence of a link between deflation and depression is the Great Depression (1929-34). We find virtually no evidence of such a link in any other period. … What is striking is that nearly 90% of the episodes with deflation did not have depression. In a broad historical context, beyond the Great Depression, the notion that deflation and depression are linked virtually disappears.3

If deflation does not cause recessions (or depressions as they were known prior to World War II), what does? And why was it so prominently featured during the Great Depression? According to economists of the Austrian School of economics, recessions share the same source: artificial inflation of the money supply. The ensuing “malinvestment” caused by synthetically lowered interest rates is revealed when interest rates resort to their natural level as determined by the supply and demand of savings.

In the resultant recession, if fractional-reserve-based loans are defaulted or repaid, if a central bank contracts the money supply, and/or if the demand for money rises significantly, deflation may occur. More frequently, however, as central bankers frantically expand the money supply at the onset of a recession, inflation (or at least no deflation) will be experienced. So deflation, a sometime symptom, has been unjustly maligned as a recessionary source.

But today’s central bankers do not share this belief. In 2002, Ben Bernanke opined that “sustained deflation can be highly destructive to a modern economy and should be strongly resisted.”4 The current Federal Reserve chair, Janet Yellen, shares his concerns:

… it is conceivable that this very low inflation could turn into outright deflation. Worse still, if deflation were to intensify, we could find ourselves in a devastating spiral in which prices fall at an ever-faster pace and economic activity sinks more and more.5

Now unmoored from any gold standard constraints and burdened with massive government debt, in any possible scenario pitting the spectre of deflation against the ravages of inflation, the biases and phobias of central bankers will choose the latter. This choice is as inevitable as it will be devastating.

Endnotes:

- Krugman, Paul. “Why is Deflation Bad?” [2] The Conscience of a Liberal. The New York Times 2 August 2010.

- McCusker, John J. “How Much Is That in Real Money?: A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States.” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, Volume 101, Part 2, October 1991, pp. 297–373.

- Atkeson, Andrew and Kehoe, Patrick. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Deflation and Depression: Is There an Empirical Link? January 2004.

- Bernanke, Ben.“Deflation: Making Sure ‘It’ Doesn’t Happen Here.” Remarks by Governor Ben S. Bernanke Before the National Economists Club, Washington, D.C. 21 November 2002. [3]

- Yellen, Janet. A View of the Economic Crisis and the Federal Reserve’s Response [4], Presentation to the Commonwealth Club of California. San Francisco, CA 30 June 2009.

Links:

[1] https://mises.org/profile/christopher-p-casey

[3] http://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/speeches/2002/20021121/

There is No Tradeoff Between Inflation and Unemployment

Mises.org

Publish Date: June 5, 2014 – 12:00 AM

Author 1: Christopher P. Casey [1]

Anyone reading the regular Federal Open Market Committee press releases can easily envision Chairman Yellen and the Federal Reserve team at the economic controls, carefully adjusting the economy’s price level and employment numbers. The dashboard of macroeconomic data is vigilantly monitored while the monetary switches, accelerators, and other devices are constantly tweaked, all in order to “foster maximum employment and price stability.”1 The Federal Reserve believes increasing the money supply spurs economic growth, and that such growth, if too strong, will in turn cause price inflation. But if the monetary expansion slows, economic growth may stall and unemployment will rise. So the dilemma can only be solved with a constant iterative process: monetary growth is continuously adjusted until a delicate balance exists between price inflation and unemployment. This faulty reasoning finds its empirical justification in the Phillips curve. Like many Keynesian artifacts, its legacy governs policy long after it has been rendered defunct.

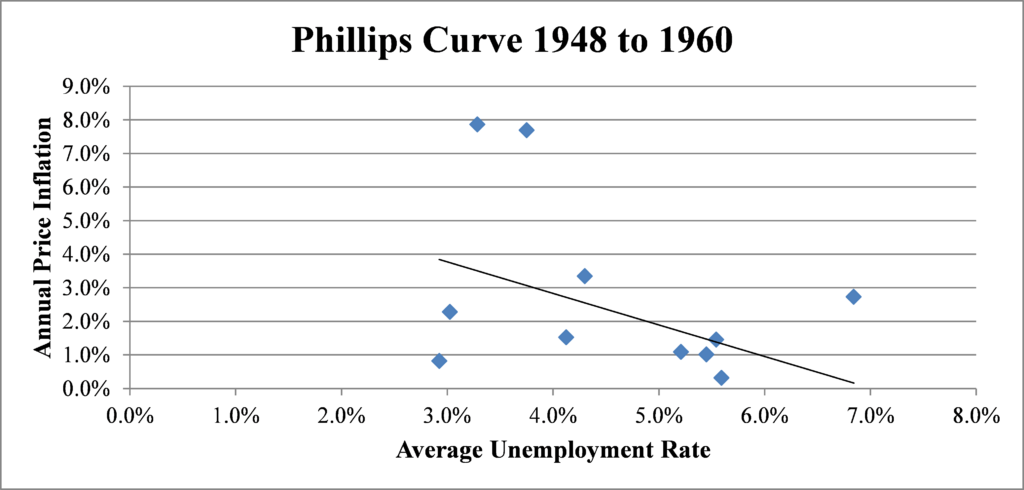

In 1958, New Zealand economist William Phillips wrote The Relation between Unemployment and the Rate of Change of Money Wage Rates in the United Kingdom, 1861–1957.2 The paper described an apparent inverse relationship between unemployment and increases in wage levels. The thesis was expanded in 1960 by Paul Samuelson in substituting wage levels with price levels. The level of price inflation and unemployment were thereafter linked as opposing forces: increasing one decreases the other, and vice versa. The US data from 1948 through 1960 comparing the year-over-year increases in the average price level with the average annual unemployment rate seemed irrefutable:3

The first dent in the Phillips curve came from Chicago-School economist Milton Friedman (as well as, independently, Edmund Phelps) who suggested it was more temporary than timeless, more illusion than illustration. Friedman’s “fooling model” posited that price inflation fooled workers into accepting employment at “higher” wage rates despite lower real rates as measured after the impact of price inflation. Once they realized the difference between “real” and “nominal” wages (the fools!), they would demand higher nominal rates as compensation. As inflation rose, unemployment declined, but only temporarily until a new equilibrium was achieved. This simple insight created quite a stir and troubled noted econo-sadist Paul Krugman: “when I was in grad school, I remember lunchtime conversations that went something like this; ‘I just don’t buy the … stuff — it’s not remotely realistic.’ ‘But these people have been right so far, how can you be sure they aren’t right now?’”4

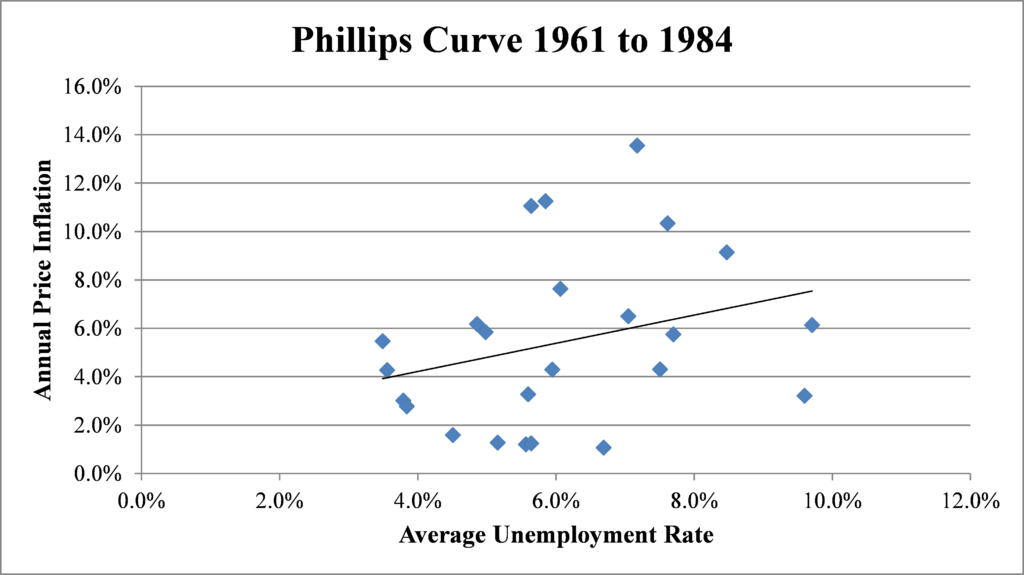

The Friedman criticism was somewhat clever, but unnecessary, minor, and misguided, for cold data was far more damaging than Chicago doctrine. The Phillips curve not only evaporated with the 1970s, but reversed to show a positive correlation between price inflation and unemployment:

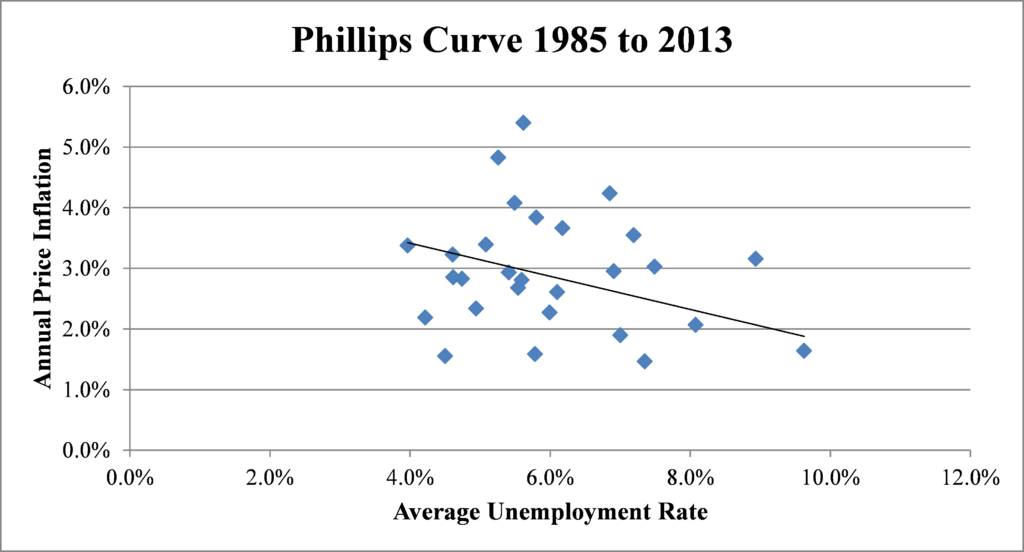

In light of this, like many Keynesian concepts, the Phillips curve should have been forever abandoned when the 1970s proved high price inflation and unemployment rates can coexist. But now the Phillips curve is back from the dead. Krugman, writing in 2013, introduced new data demonstrating the Phillips curve’s “resurrection.” According to Krugman: How many economists realize that the data since around 1985 — that is, since the Reagan- Volcker disinflation — actually look a lot like an old-fashioned Phillips curve?

This Krugman comment is correct, US data from 1985 through 2013 again shows an inverse correlation between the year-over-year increases in the average price level with the average annual unemployment rate:

Has the Phillips curve, as Krugman suggests, regained its former acceptance? Since 1985, why has its inverse relationship between price inflation and unemployment reappeared? The question is irrelevant: the fact that it had previously disappeared forever strips the Phillips curve of legitimacy.

Any apparent correlation between two variables may be coincidental and unrelated, directly casual, or linked by a third variable or sets of variables. For price inflation and unemployment, the last explanation is the correct one. Price inflation and unemployment are not opposing forces, but in large part effects deriving from the same causation — the expansion of the money supply.

More money cheapens its value and the price of goods and services accordingly rise in terms of money — hence price inflation. More money lowers interest rates which induce malinvestments (including the hiring of workers) which (who) are eventually liquidated (terminated) in a recession — hence unemployment. While both phenomena largely share a common origin, the timing of their manifestations may be quite different and heavily dependent upon other variables, including fiscal policy.

The death of the Phillips curve will eventually be served not from Chicago School gimmicks, not from the experience of the 1970s, but from greater acceptance of the Austrian School’s explanations of price inflation and business cycles. Unfortunately, in the interim, the monetary policies promoted by the Phillips curve have moved from 1970s lunchtime academic discussion to official government policy. In the hands of the Federal Reserve, the Phillips curve becomes weaponized Keynesianism.

Due to its unjustified acceptance of the Phillips curve and its related misconceptions about price inflation and business cycles, the Federal Reserve will never be able to trade higher price inflation for lower unemployment. Nor can it sacrifice higher unemployment for lower price inflation. But it can, and likely will, generate high levels of both. If the Federal Reserve’s economic controls appear broken, it is because they never really worked in the first place.

Endnotes:

- Press release [2]. Federal Open Market Committee. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. 30 April 2014.

- William Phillips, “The Relation between Unemployment and the Rate of Change of Money Wage Rates in the United Kingdom, 1861–1957,” Economica 25, No. 100 (1958): 283–299.

- Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. In the interest of aesthetics and clarity, years for which a negative price inflation or unemployment rate have been excluded. However, their visual exclusion does not alter the linear trendline presented in the following graphs.

- Paul Krugman, “More Paleo-Keynesianism (Slightly Wonkish),” [3] The Conscience of a Liberal. The New York Times 16 December 2013.

Why the Wealth Effect Doesn’t Work

Mises.org

Publish Date: March 11, 2014 – 12:00 AM

Author 1: Christopher P. Casey [1]

Higher equity prices will boost consumer wealth and help increase confidence, which can spur spending. — Ben Bernanke, 2010.1

Across all financial media, between both political parties, and among most mainstream economists, the “wealth effect” is noted, promoted, and touted. The refrain is constant and the message seemingly simple: by increasing people wealth through rising stock and housing prices, the populace will increase their consumer spending which will spur economic growth. Its acceptance is as widespread as its justification is important, for it provides the rationale for the Federal Reserve’s unprecedented monetary expansion since 2008. While critics may dispute the wealth effect’s magnitude, few have challenged its conceptual soundness.2 Such is the purpose of this article. The wealth effect is but a mantra without merit.

The overarching pervasiveness of wealth effect acceptance is not wholly surprising, for it is a perfect blend of the Monetarist and Keynesian Schools.3 While its exact parentage and origin appears uncertain, its godfather is surely Milton Friedman who published his permanent income theory of consumption in 1957.4 In bifurcating disposable income into “transitory” and “permanent” income, Friedman argued the latter dictates our spending and consists of our expected income in perpetuity. If consumer spending is generated by expected income, then surely it must also be supported by current wealth?

But this may or may not be true. It will vary across time, place, and among various economic actors whose decisions about consumer spending are dictated by their time preferences. And time preferences — the degree to which an individual favors a good or service today (consumption) relative to future enjoyment — take into account far more variables than the current, unrealized wealth reported in brokerage statements and housing appraisals.

Regardless as to whether or not increased wealth will actually spur increased consumer spending, the most important component of the wealth effect is the assumption that increased consumer spending stimulates economic growth.5 It is this Keynesian concept which is critical to the wealth effect’s validity. If increased consumer spending fails to stimulate the economy, the theory of the wealth effect fails. Wealth effect turns into wealth defect.

Will increased consumer spending improve the economy? On one side of the argument, we have the aggregate individual conclusions of hundreds of millions of economic actors, each acting in their own best interest. These individuals and businesses are attempting to reduce consumer spending and increase savings.

Dissenting from their views are the seven members of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve. Each member believes in the paradox of thrift — the belief that increased savings, while beneficial for any particular economic actor, have deleterious effects for the economy as a whole. The paradox of thrift can essentially be described as such: decreased consumer spending lowers aggregate demand which reduces employment levels which negatively affects consumption which in turn lowers aggregate demand. The paradox predicts an economic death spiral from diminished demand. And mainstream economists believe we were (and potentially are) mired in such a spiral. As noted econo-sadist Paul Krugman noted in 2009: “we won’t always face the paradox of thrift. But right now it’s very, very real.”6

The inverse of this “reality” predicts flourishing economic prosperity when a society increases its consumer spending. But history suggests the opposite: it is higher savings rates which lead to economic prosperity. Examine any economic success story such as modern China, nineteenth century America, or post-World War II Japan and South Korea: did their economic rise derive from unbridled consumption, or strict frugality? The answer is self-evident: it is the savings from the curtailment of consumption, combined with minimal government involvement in economic affairs, which generates economic growth.

So why do so many “preeminent” economists falsely believe in the paradox of thrift, and thus the wealth effect? It is because of their mistaken understanding of the nature of savings. The Austrian economist Mark Skousen addressed this in writing:

Savings do not disappear from the economy; they are merely channeled into a different avenue. Savings are spent on investment capital now and then spent on consumer goods later.7

Savings are spent. Not directly by consumers on electronics and espressos, but indirectly by businesses via banks on more efficient machinery and capital expansions. Increased savings may (initially) negatively affect retail shops, but it benefits producers who create the goods demanded from the increased pool of savings. On the whole, the economy is more efficient and prosperous.

Does this economic maxim hold even when the economy is in a recession?8 Even more so. As all Austrian economists know, business cycles derive from government manipulation of the money supply which artificially lowers and distorts the structure of interest rates.9 To minimize the length and severity of a recession, economic actors should save more which will reduce the gap between artificial and natural rates of interest.

Regrettably, this is not merely an academic discussion. Due to their mistaken economic beliefs, the Federal Reserve has quadrupled the money supply while bringing interest rates to historic lows.10 The results will inevitably arise: significant price inflation, volatile financial markets, and severe economic downturns. In many respects, Sir Francis Bacon’s aphorism that “knowledge is power” is true. Unfortunately, in the economic realm, the Austrian economist F.A. Hayek was closer to the truth: those in power possess the pretense of knowledge.11

Endnotes:

- Ben S. Bernanke, “Op-Ed Columnist — What the Fed Did and Why: Supporting the Recovery and Sustaining Price Stability. [2]” The Washington Post. 4 November 2010.

- To date, most criticism focuses on the relatively minor increase in real GDP (11.2 percent from April 1, 2009 through October 1, 2013) relative to the substantial increases in the money supply and the stock market which have risen, respectively, 330.0 percent (Adjusted Monetary Base from August 1, 2008 through January 1, 2013) and 160.9 percent (S&P 500 from March 1, 2008 through February 19, 2014). The dates have been selected to measure the increase since the respective lows reached subsequent to August 1, 2008 to the most recent data.

- The characterization of monetarism as an economic school can be disputed. By definition, a school of thought must be systemic, which means positions and theorems must be connected by underlying assumptions. The so-called Monetarist School consists of various unrelated hypotheses which are empirically “tested.” While the preponderance of the “school’s” positions may favor free markets (although often not for the most critical markets — e.g., money), they display inconsistency in application. This underscores the lack of an academic edifice built from fundamental axioms.

- Milton Friedman, Theory of the Consumption Function. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press; Homewood, Ill.: Business One Irwin. 1957.

- The commonly cited support for this assertion, that personal consumption accounts for approximately 70 percent of Gross Domestic Product is, strictly speaking, correct. However, it is correct only because GDP overstates personal consumption as a by-product of a misguided attempt to avoid “double counting.” If non-durable capital goods and intermediate products (e.g., steel) were included in GDP (as they should be if one is attempting to measure economic activity), personal consumption would fall to approximately 40 percent of economic activity based upon the latest GDP component and Gross Output statistics. Mark Skousen, “Beyond GDP: Get Ready For A New Way To Measure The Economy.” Forbes. 29 November 2013.

- <http://www.forbes.com/sites/realspin/2013/11/29/beyond-gdp-get-ready-for-a-new-way-to-measure-the-economy/#!>

- Paul Krugman, “The Paradox of Thrift — for Real. [3]” The Conscience of a Liberal. The New York Times. Web. 7 July 2009.

- Mark Skousen, Economics on Trial. Homewood, Ill.: Business One Irwin, 1991. p. 54.

- It would be odd indeed if one argued that savings increases economic growth during normal times, but exiting a recession requires greater levels of consumption. As Ayn Rand wrote: “Contradictions do not exist. Whenever you think you are facing a contradiction, check your premises. You will find that one of them is wrong.” (Atlas Shrugged, New York: Random House, 1957). If economic growth during a recession requires increased consumption, then this business cycle theory does not comport with general economic theory — which is prima facie evidence that it is wrong.

- It should be noted that an increase in consumer spending due to increased levels of real or perceived wealth in no way invalidates or contradicts Austrian business cycle theory (“ABCT”). While some economists have alleged increased consumption during the boom phase of a business cycle is in conflict with ABCT, Austrian economist Joseph Salerno has effectively squashed such criticisms as a misinterpretation. (Joseph Salerno, “A Reformulation of Austrian Business Cycle Theory in Light of the Financial Crisis,” Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics. 15, No.1. [2012]).

- See footnote 2.

- “To act on the belief that we possess the knowledge and the power which enable us to shape the processes of society entirely to our liking, knowledge which in fact we do not possess, is likely to make us do much harm.” F.A. Hayek, “The Pretense of Knowledge.” Lecture to the Memory of Alfred Nobel. Stockholm Concert Hall. Stockholm, Sweden. 11 December 1974.

Links:

[1] https://mises.org/profile/christopher-p-casey

[2] “http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/11/03/AR2010110307372.html”

[3] ”http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/07/07/the-paradox-of-thrift-for-real/?r=0”

Scenarios for Owning Gold

Part III of the V Part Series,Why Gold?

Brett K. Rentmeester, CFA ®, CAIA ®, MBA – brett.rentmeester@windrockwealth.com

Gold serves a unique role in investment portfolios, not only as insurance against extreme events, but as a timeless store of value in a world of multiplying paper currency. Why own gold? In simple terms, gold has been a store of value for thousands of years because it has retained its purchasing power while “fiat”

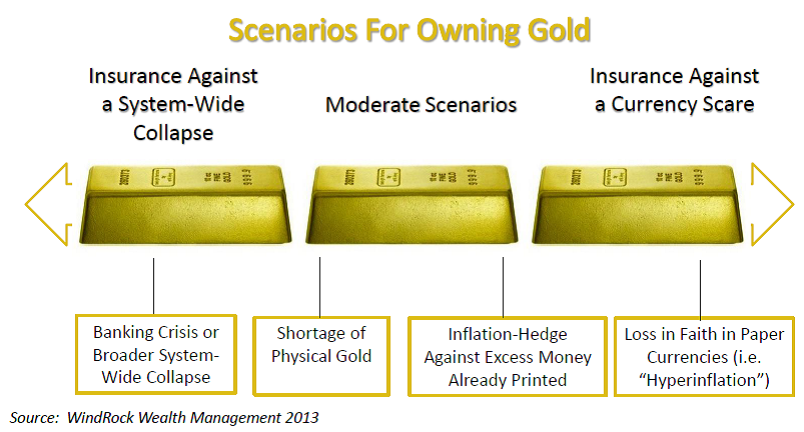

currencies, which are promises unbacked by precious metals, have eventually been overprinted and seen their value diminish or completely disappear. Gold is a currency that has no liabilities, is outside of the fragile global banking system, and cannot be printed out of thin air like other currencies. Gold is a particularly important asset to own when money is being printed as carelessly as it is today. Policy actions today heavily increase the odds of more extreme events in the future that should be keeping all investors up at night. Many investors view gold as “insurance” against extreme scenarios, which we address below. While true, they miss the multiple scenarios for owning gold, not all of which involve an extreme outcome to recommend it as a key holding.

Extreme Scenarios

Banking Crisis or System-Wide Collapse – Is a renewed banking crisis a valid concern to worry about today? Absolutely. The world was on the verge of the largest global banking collapse in modern history in 2008. Trillions of dollars were printed to paper over the problems, but the central issues still remain. At the center is the fact that modern-day banks act more like highly leveraged hedge funds than traditional lenders. With financial derivatives nearing 10 times global gross domestic product (i.e. GDP), the global banking system remains highly leveraged and susceptible to any spark that could ripple through the system.[1] A new worry has emerged for savers as the recent “bail-in” in Cyprus led to the seizure of nearly 50% of deposits held by savers over €100,000. Many other countries are working on legislation that may allow for future bail-ins as well (including the Europe Union, Canada and the U.S.). With this risk in mind, the idea of holding cash at a bank where it earns 0% and could someday be seized makes gold held outside of the banking system an increasingly attractive alternative for concerned savers. As the entire developed world continues to print money to manipulate markets higher in the absence of healthy organic growth, the risks of a systematic global banking crisis continue to rise. However, we believe that policy makers looked over the cliff of a global banking crisis in 2008 and decided they would print as much money as necessary to avoid that fate. Thus, events moving us closer to a banking crisis actually increase the odds for the opposite outcome – that policy makers print even more money, aiding the banks, but panicking investors about inflation.

Central banks have one potential “ace in their pocket” if we see renewed banking scares, but it is not a card they want to play. If a banking crisis lies ahead, policy makers will be desperate to do whatever they can to restore faith in the system. If the printing of money fails to deliver stability, then the reinsertion of gold into the currency system could be their Plan B. Napoleon successfully reinserted gold into the failing currency system during the French Revolution to restore faith. He stated “while I live I will never resort to irredeemable paper.”[2] In our opinion, policy makers would only take this action in a worst-case scenario where they have lost control of the system. As we discussed in our earlier pieces, re-backing the dollar with gold (as an example) at ratios similar to the 1930s could propel gold upwards of $8,000 per ounce.[3]

Loss of Faith in Currencies – If one extreme is a banking crisis and corresponding credit crunch, then the other extreme is a loss of faith in the fiat money system itself, a condition known as “hyperinflation”. History suggests that once central banks start printing money of significant magnitude, it is very hard to reverse course. This is because the effects of printed money serve to prop markets up artificially. Ultimately, policy makers get backed into a corner where the act of pulling back the support of easy money risks collapsing the overleveraged system from artificial levels. We believe this is the dilemma policy makers are facing today as they have become the buyer of last resort in many markets. For example, the Federal Reserve is now the buyer of over 90% of all newly issued treasury bonds, which has artificially suppressed interest rates and led to other assets rising on the opium of cheap credit.[4] At some point, the continued manufacturing of money out of thin air risks hitting a psychological breaking point. People may suddenly wake up to the reality that newly printed money is diminishing the value of their existing money. If history is a guide, the response is to swap their currency into hard or tangible assets as an alternative store of value since these assets are in relatively fixed supply versus the exploding supply of currency. At this point, the rate at which money changes hands in the economy (i.e., the velocity of money), which has been subdue since 2008, suddenly skyrockets and inflation soars. “Not worth a Continental” is a phrase many investors have heard before, but too few know its historical relevance. America’s Revolutionary War-era currency, the Continental, was issued in an amount equal to one dollar. By 1779, after being overprinted to fund war with England, it was worthless.[5] Weimar Germany after World War I is the poster child of this risk. They faced plunging their economy into a depression by stopping the printing presses, so they ultimately chose to print more money. For a period of time, it appeared to work. Their actions propped up the system, reduced unemployment, and gave the appearance of growth, until it ultimately buckled under its own weight and collapsed. Adam Fergusson, in his book When Money Dies: The Nightmare of the Weimar Collapse, wrote:

Money is no more than a medium of exchange. Only when it has a value acknowledged by more than one person can it be so used. The more general the acknowledgement, the more useful it is. Once no one acknowledged it, the Germans learnt, their paper money had no value or use.[6]

Investors today must recognize that we are conducting the largest monetary experiment in modern history with unknown consequences. We are not suggesting that these extreme scenarios are likely outcomes. However, we are suggesting that, in today’s uncertain world dominated by money printing and government manipulation, these scenarios require a serious level of understanding. Despite shielding their views from the investment public at large, our experience suggests the smartest investment minds speak of these fears behind closed doors.

Moderate Scenarios

Shortage of Physical Gold — There is compelling evidence suggesting that there is not enough physical gold relative to the amount of paper contracts written on it today. Some reports suggest that as many as 100 contracts of paper gold exist for every one bar of physical gold.[7] To benefit from this, investors do not need an extreme outcome to see the value of gold unlocked, but they do need to own the actual physical metal. Many investors think they own gold, but what they actually own are paper contracts with no ability to receive the actual physical gold. Recent actions by global banks such as ABN AMRO are early warnings that cracks may be developing in the gold market. They defaulted on delivering physical gold to clients who owned it (instead redeeming them in cash).[8] These paper claims dwarf the amount of physical gold that can be found at today’s prices. Paper claims include most precious metals mutual funds and exchange traded funds (“ETFs”) and gold held in “unallocated” bank accounts (i.e. those not held in the legal title of the account holder, but commingled with other investors on the balance sheet of a financial institution). Prospectuses of most ETFs allow redemption in cash to investors. Thus, this could result in an investor being redeemed out of their gold holding at an inopportune time well before gold reaches its peak value. The gold market mimics the fractional-reserve banking system in that a small amount of physical gold underlies many paper claims. As more investors realize this, there could be a scramble to secure the actual physical gold, driving prices up significantly. Under these conditions, we’d expect a wide premium to develop benefitting physical gold over paper claims on gold that can’t deliver the underlying metal. Compounding matters is the fact that gold is commonly leased out by central banks around the world. This makes it hard to accurately analyze who actually owns the gold as messy international accounting rules allow more than one party to claim the same gold on their respective balance sheets. Leading investment minds, such as Eric Sprott of Sprott Asset Management, have extensively investigated this issue, posing the question, “do western central banks have any gold left?”[9] We believe there is much less physical gold available than meets the eye – at least at today’s prices.

The physical shortage will accelerate as more investors include precious metals as a component of their portfolios. In addition to investor demand, governments around the world continue to increase their holdings of gold, especially countries like China where gold represents only a small portion of their reserves today. For those that doubt the viability of gold as an asset, it is instructive to see what the governments of countries bailing out other weaker countries generally require for collateral – a country’s gold! There is also a camp of thought suggesting there could even be a hidden game underway today, orchestrated by policy makers. Central banks may be active in suppressing the price of gold in the paper derivatives markets as they quietly accumulate physical gold on the cheap. Some believe that once they own the majority of physical metal on their balance sheets, they will cease these actions and gold will be revalued suddenly, perhaps over a weekend. This would suddenly give them a valuable asset to offset many of their liabilities. If this is true, the problem is that too few investors will be holding any physical gold at the time to benefit.

Hedge Against Inflation – Without having to assume any type of extreme scenario, gold will be a good investment if the world keeps printing money to try and solve its problems. We believe they will keep printing as the lessor of evils. Printing money will lead to a decline in the value of currencies versus gold, stoking inflation as devalued currencies buy fewer goods. This is the number one reason to own gold – as a hedge against central bank risk and the overprinting of money. We believe that irrespective of money printing ahead, the reckless printing since 2008 already makes currency devaluation versus gold a high probability event. Historical data suggests that inflation often follows money supply growth, but with a lag. Since 2008, we have increased the money supply upwards of 260% in the US.[10] In addition, we are currently printing approximately $1 trillion dollars a year as our long-term liabilities continue to grow out of control. To us, this suggests a high risk of inflation ahead at a time when inflation-protected investments are very cheap and unloved by investors.

In closing, gold is not a one-trick pony. Own gold for the likely moderate scenarios, but rest assured that gold is the best asset if we get pushed to the extremes.

Endnotes:

- “A Hedge Fund Economy” WindRock Wealth Management. Web. August 2013. <https://windrockwealth.com/blogs/item/127-a-hedge-fund-economy>.

- Murenbeeld, Martin. “Gold Monitor” DundeeWealth Inc. Web. 5 April 2013. <http://www.dundeewealthus.com/en/Institutional/Economic-Market-Commentary/Index.asp>. Pg. 4.

- Kruger, Daniel and McCormick, Liz Capo. “Treasury Scarcity to Grow as Fed Buys 90% of New Bonds.” Bloomberg. Web. 12 December 2012. <http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-12-03/treasury-scarcity-to-grow-as-fed-buys-90-of-new-bonds.html>.

- Rothbard, Murray. A History of Money and Banking in the United States (Auburn, Alabama: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2002), pgs. 59-60.

- Fergusson, Adam. When Money Dies: The Nightmare of the Weimar Collapse (London: William Kimber: 1975), p. 312

- Naylor-Leyland, Ned. Cheviot Asset Management. Interview with CNBC Europe. Web. 23 December 2011. <http://www.cheviot.co.uk/media/press/outlook-gold- 2012>.

- “Largest Dutch Bank Defaults on Physical Gold Deliveries to Customers.” Clarity Digital Group LLC d/b/a Examiner.com. Web. 3 April 2013. <http://www.examiner.com/article/largest-dutch-bank-defaults-on-physical-gold-deliveries-to-customers>.

- Baker, David and Sprott, Eric. “Do Western Central Banks Have Any Gold Left???” Sprott Global Resource Investments Ltd. Web. September 2012. < http://sprottglobal.com/markets-at-a-glance/maag-article/?id=6590>

- Casey, Christopher. “Inflation: Why, When, and How Much” WindRock Wealth Management. Web. July 2013. <https://windrockwealth.com/inflation-why-when- how-much>.

Brett K. Rentmeester, CFA ®, CAIA ®, MBA is the President and Chief Investment Officer of WindRock Wealth Management (www.windrockwealth.com). Mr. Rentmeester founded WindRock Wealth Management to bring tailored investment solutions to investors seeking an edge in an increasingly uncertain world. Mr. Rentmeester can be reached at 312-650-9593 or at brett.rentmeester@windrockwealth.com.

All content within this article is for information purposes only. Opinions expressed herein are solely those of WindRock Wealth Management LLC and our editorial staff. Material presented is believed to be from reliable sources; however, we make no representations as to its accuracy or completeness. All information and ideas should be discussed in detail with your individual adviser prior to implementation.