And the Election Winner is … Inflation in a Landslide!

Christopher P. Casey

Regardless as to which candidate secures the Presidency on November 3rd (or some subsequent date), the administration must cope with unprecedented federal debt. This debt will only increase for the foreseeable future with record-breaking federal deficits caused by mounting pandemic relief and stimulus spending along with diminished tax revenues. The only available “solution” for the U.S. government to finance such debt and deficits will be through continued massive money printing which will inevitably lead to price inflation. How can investors protect themselves?

What Does and Does Not Cause Inflation?

Due to the widespread misunderstanding of what causes inflation, it first warrants a discussion as to what does not cause inflation. In particular, three inflation fallacies are often cited by mainstream financial pundits and Keynesian economists.

First, the “cost-push” theory of inflation states that price increases in certain commodities force the prices of all goods and services higher. The 1970s are often cited as an example: as increased oil prices permeated the economy, prices for fuel, plastics, and other oil-derived products would increase as well.

But as the price of oil or some other cost-push culprit rises, buyers have less money to spend on other goods and services. Having less money to purchase something else means less demand exists for that other product, and decreased demand reduces prices. So, while some prices may go up, it is ultimately at the expense of other prices which go down. Accordingly, no direct net effect to the overall price level is created by these price changes.

The second inflation misconception is the “demand-pull” theory. Keynesian economic theory believes inflation also materializes when aggregate demand for goods and services exceeds aggregate supply when the economy is at full employment and capacity (which also incorrectly assumes such “aggregates” can diverge from each other). When the economy is at full employment and capacity, increased aggregate demand forces producers of goods and services (soon to be followed by their suppliers) to increase prices. Here lies the origin of the belief in inflation from an “overheated” economy. According to this theory, inflation cannot develop during periods of weak economic growth. But the 1970’s American economy (as well as numerous other economic periods in history – see modern-day Venezuela) clearly disprove this.

Finally, many incorrectly believe inflation cannot develop until the “velocity” of money increases. Typically defined as “the number of times one dollar is spent to buy goods and services per unit of time,” monetary velocity theory originates from the so-called Fisher Equation of Exchange: MV=PT (where the quantity of money [M] times the velocity of its circulation [V] equals prices [P] multiplied by their related transactions [T]). But why would such a formula explain the general price level?

Almost all economists today recognize that the price for any particular good or service derives from the interaction of supply and demand. The “price” of money derives from the same supply and demand dynamic as any good or service. The word “price” in terms of money, to avoid confusion, can be thought of as “value”. If the demand for money increases, its value increases and the prices of all goods and services fall (deflation). If the supply of money increases, its value decreases and the prices of all goods and services rise (inflation). Inflation is simply caused by an increase in the money supply and/or a reduction in the demand for money.

Velocity is not a substitute for demand, but rather of volume. Lots of goods and services may transact at low prices just as they may trade at high prices. In either scenario, “velocity” is high while the demand for money may be low or high. Since velocity is not a substitute for demand, it cannot help explain inflation.

How Does the Federal Debt Situation Affect Inflation?

Federal debt can be deleterious for many reasons. Among other things, it crowds out private investment (by bidding up the price of capital) and must be repaid by taxpayers (in one form or another). The repayment must derive from future taxes or by printing new money to satisfy debt service.

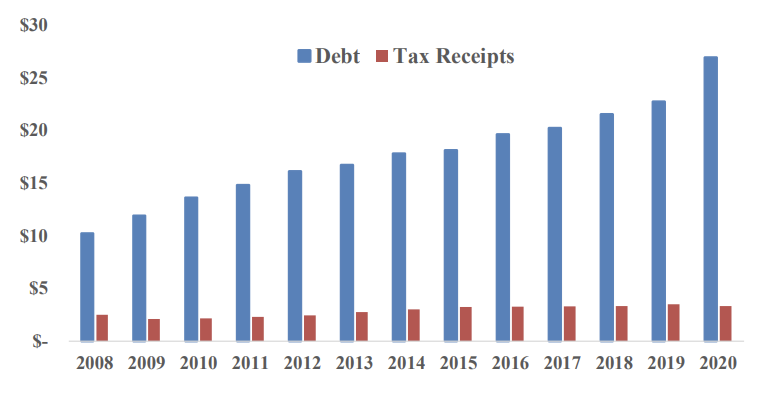

As this chart demonstrates, the U.S. government can never repay its debt based upon tax receipts (nor do politicians have any intention of doing so) (in trillions):1

As of September 30, 2020, the federal debt stood at over eight times estimated 2020 fiscal year tax receipts.2

It would take that many years to repay all debt assuming the federal government ceased all spending. Paying back the federal debt through future budget surpluses is unrealistic. And the situation is getting worse.

The Congressional Budget Office, itself always opportunistic about government finances, recently stated “the deficit in 2021 is projected to be 8.6 percent of GDP.” And that “between 1946 and 2019, the deficit as a share of GDP has been larger than that only twice”.3

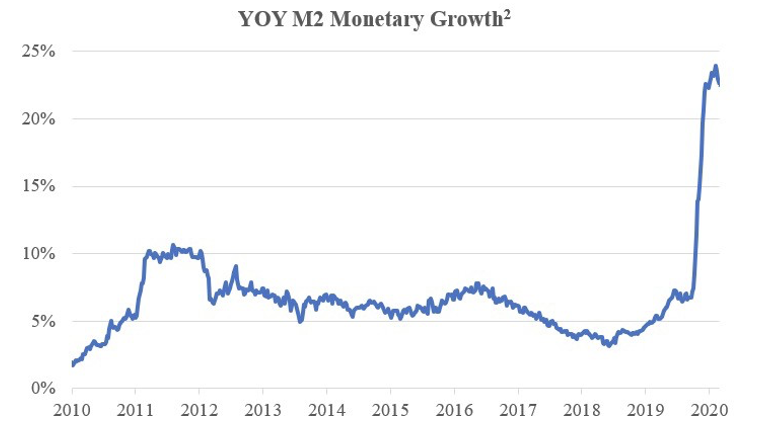

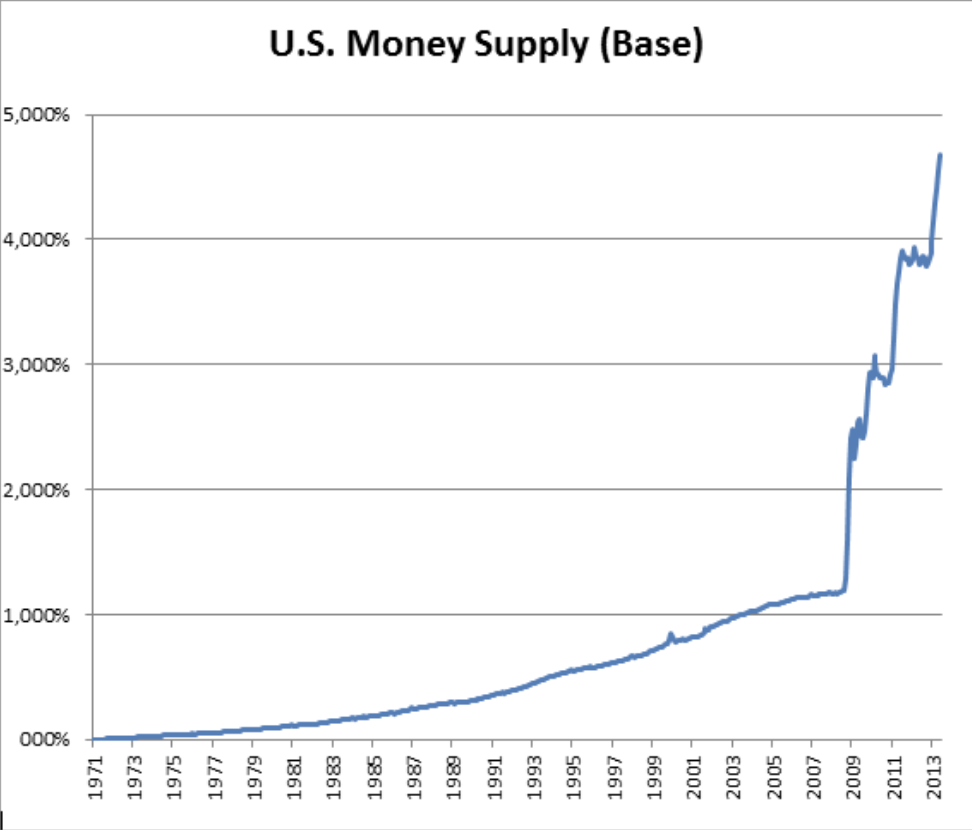

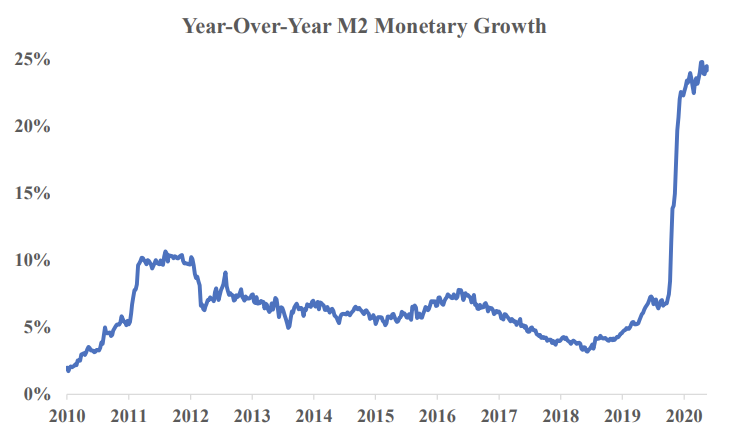

The only means by which the U.S. government can service its debt, let alone its future debt, is through continued, massive monetary expansion. And the Federal Reserve has already started in record-breaking fashion:4

Why Should Investors be Concerned?

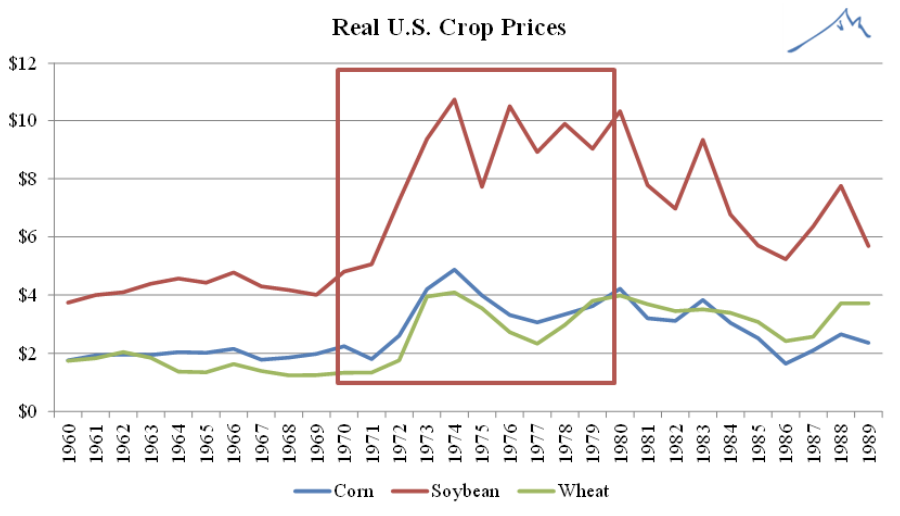

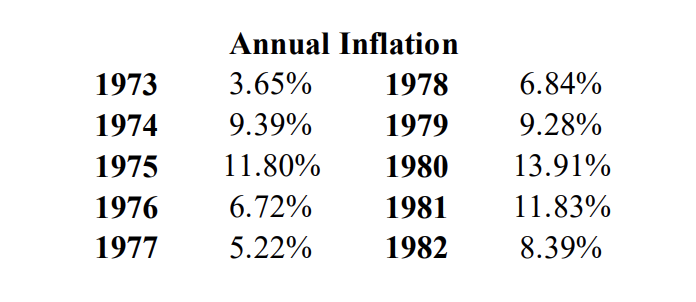

Many U.S. investors have little memory of the 1970’s inflation and thus not only discount the likelihood of inflation, but are largely ignorant as to its negative impact. It bears remembering that the price level did in fact more than double (121% increase) in approximately ten years (from 1973 to 1982).5

The implications for traditional stock and bond portfolios can be devastating. For example, in real terms, a 60%/40% stock/bond portfolio from 1973 to 1982 returned an annual rate of less than 1% (when calculated using the Wilshire 5000 Total Market Index as a proxy for equities and the ICE Bank of America U.S. Corporate Index Total Return Index Value to represent bonds).6

Bonds were especially impacted, losing just over 4% per annum which disproportionately affected retirees, those approaching retirement, and any “conservative” investors.

The 1970s demonstrate that, at least in regards to inflation, stocks and bonds may not provide significant diversification to each other.

What can Investors do to Protect Themselves from Inflation?

Inflation-protection hedges fall into three categories. First, and perhaps most obvious, alternative currencies which are not experiencing the same inflationary pressures. For many years, foreign currencies such as the Swiss franc qualified (until the Swiss National Bank embarked on the same reckless monetary expansion as the world’s other major central banks). But precious metals and cryptocurrencies provide even better protection.

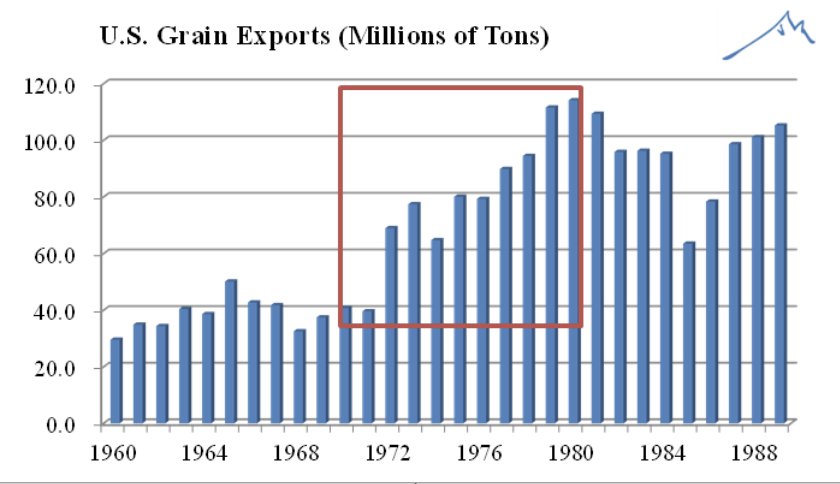

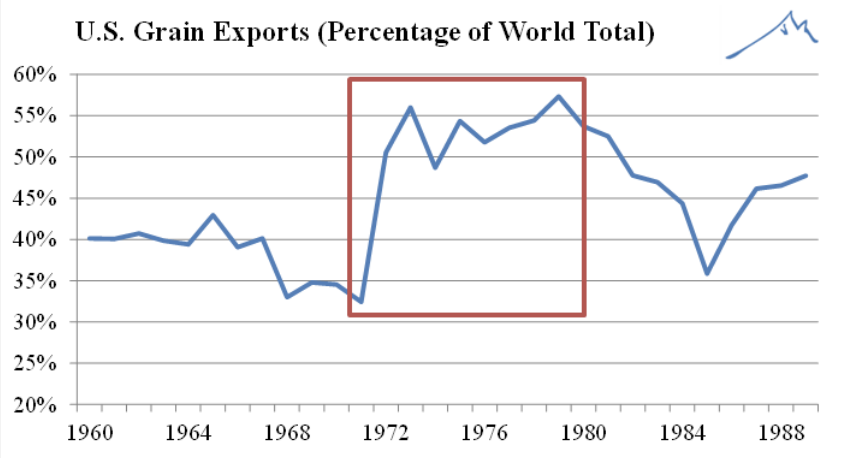

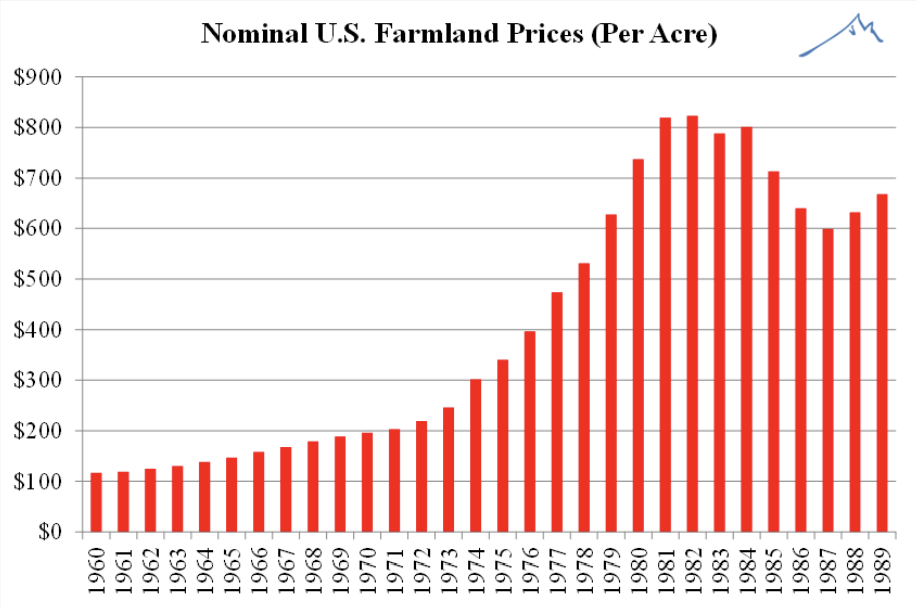

Second, any businesses which have costs in an inflationary currency with revenues tied to a stable (or at least less inflationary) currency profit from the currency valuation discrepancies, and should appreciate dramatically. Primarily, this involves commodity producers such as farmland or energy companies. Some potential examples would be American farmland in the 1970s (and in the future), Brazilian farmland today, or Russian energy companies during any ruble crisis.

Finally, assets utilizing extensive financial leverage (especially with long-term fixed rates) should also perform well. Since inflation helps borrowers to the detriment of lenders (since the money repaid is worth less than when lent), industries with large debt levels such as real estate benefit (especially if they have short- term leases with tenants that renew at the new, inflationary rents). Additionally, as inflation may increase interest rates which deters or limits future borrowing, such industries may experience less future competition, all things being equal.

But the marketplace already knows about these traditional inflation hedge categories. The time to act is before the prices of inflation-protection assets are bid up once inflation appears.

About WindRock

WindRock Wealth Management is an independent investment management firm founded on the belief that investment success in today’s increasingly uncertain world requires a focus on the macroeconomic “big picture” combined with an entrepreneurial mindset to seize on unique investment opportunities. We serve as the trusted voice to a select group of high-net-worth individuals, family offices, foundations and retirement plans.

312-650-9822

Endnotes:

- Federal Reserve Board of St. Louis https://fred.stlouisfed.org/

- US Debt Clock.org https://www.usdebtclock.org/

- “An Update to the Budget Outlook: 2020 to 2030” Congress of the United States Congressional Budget Office. September 2020

- Federal Reserve Board of St. Louis https://fred.stlouisfed.org/

- Ibid.

- Ibid.