August 13, 2013

Commemoration of a Canard

“I have directed Secretary Connally to suspend temporarily the convertibility of the dollar into gold.” – Richard M. Nixon, August 15, 1971

In the spirit of commemoration, we cannot allow the 42nd anniversary of Nixon’s speech go without comment. Addressing the nation to “outline a new economic policy”, he failed to disappoint: wage and price controls were instituted, the automobile industry was browbeaten into reducing prices, and a 10% tariff was assessed on all imports. All this before Nixon announced his grandest exploit – the termination of U.S. commitments to exchange gold for dollars with foreign governments.

Previously, the Federal Reserve’s ability to issue new money was limited by the threat of depleting the government’s gold reserves. Printing too many dollars led foreign governments to start favoring gold over holding depreciating U.S. dollars. Nixon’s actions (which proved not to be temporary) ended the last vestige of a gold standard, erased all limits on the unchecked printing of money, and effectively ended the world’s currency system (known as Bretton Woods) in place since World War II.

Whether Nixon was sincere in his belief that these actions would truly, to use his terms, “nurture and stimulate” the economy or if – perchance – he knew better and deceived the American people, we have no comment. We reserve our commentary not to purpose, but to effect.

And the effect was an unmitigated disaster. Nixon promised Americans that any talk of inflation with an unconstrained Federal Reserve was a “bugaboo” and that his actions would actually “stabilize the dollar.” (If you wish to listen to Nixon in his own words, the latter part of his speech can be viewed here). According to him, the risk of Americans paying higher prices was extremely limited:

If you want to buy a foreign car or take a trip abroad, market conditions may cause your dollar to buy slightly less. But if you are among the overwhelming majority of Americans who buy American-made products in America, your dollar will be worth just as much tomorrow as it is today.

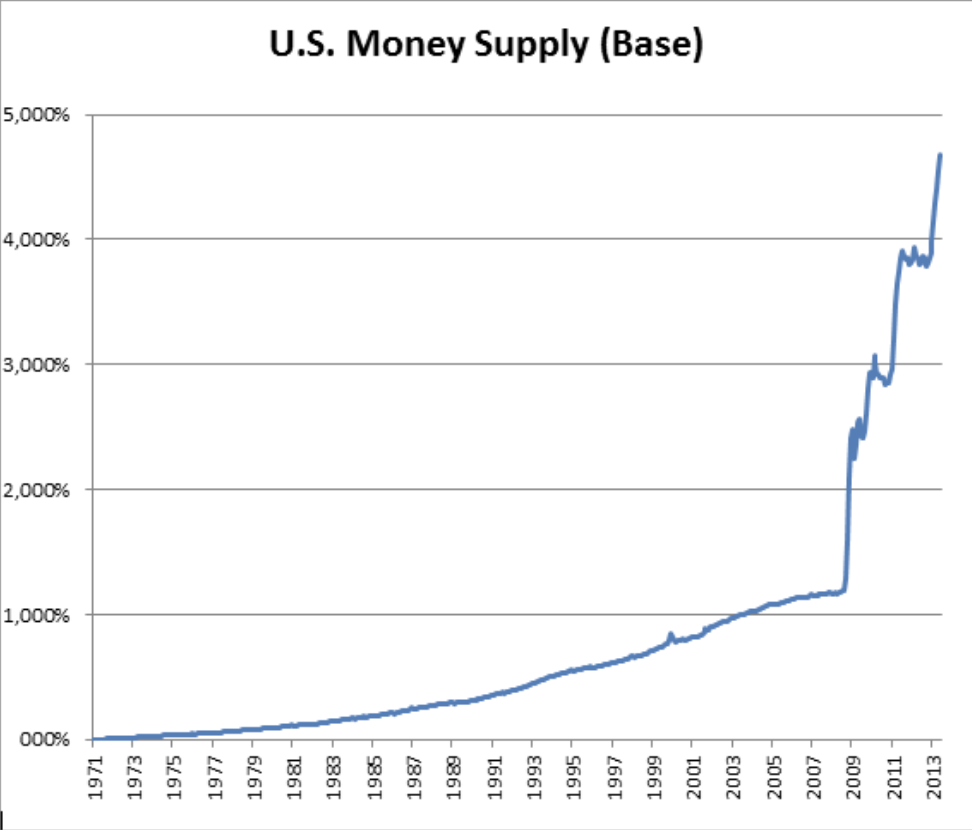

Despite these assurances, inflation became a hallmark of the 1970’s as the unimpeded Federal Reserve zealously increased the money supply. The year 1973 experienced inflation of 9%, 1974 brought 12%, and the decade was closed out with a peak inflation rate of 14% in 1979. Since the date of Nixon’s speech, the dollar has lost 83% of its value. One dollar then is worth 17 cents today. What will it be worth tomorrow?

We cannot say with certainty, for while the creation of money causes inflation, the effect does not correspond fully in magnitude. Nor is it immediate. In fact, the lag between the expansion of the money supply and the onset of inflation could be years. If so, what expectations are reasonable based upon the Federal Reserve’s actions since 2008? The scary answer can be found in this chart.

To tweak a famous quote by Winston Churchill, wiping away the last traces of the gold standard was not a new beginning for U.S. monetary policy. It was not even the end of the beginning. But it was, perhaps, the beginning of the end.