Most financial publications have an annual roundtable of Wall Street economists or mainstream financial commentators, all of whom share very similar viewpoints.

WindRock’s annual roundtable features independent investment minds.

WindRock: Let’s start with the 2021 impact of three major 2020 developments: the election, social unrest, and the Covid-imposed lockdowns. First, we have a new Biden administration with a Democratically controlled Congress. What do you think will be the most likely major legislation to pass? Will that include rolling back anything Trump did?

Mauldin: In one sense, it’s not an ideal world if you’re a Democrat. You get blamed for everything, but you don’t have a whole lot of control. Even though they technically have control of Congress, if they lose a couple of moderates, you’ve lost your majority (with the tie cast by the vice president) in the Senate. So, I don’t think they’re going to be able to go too far with their agenda. [Speaker of the House] Pelosi has the same problem. She gets five or six of her members to switch party lines on votes, and she’s lost her majority. It’s a razor-thin margin.

So, I don’t expect radical legislation. I would expect to see an infrastructure bill for which, frankly, if we’re going to run up the national debt on stimulus acts, I would rather run it up with actual, honest-to-God infrastructure. I’m talking roads, bridges – the stuff that we need to get repaired.

I would like to see the creation of something like a Ginnie Mae for infrastructure so that cities can borrow money to fix their own infrastructure. There’s a lot of cities that need to rebuild their water systems. They can tack on a penny a gallon or whatever the number would work to retire that debt if you can borrow at 1- 2%. The Fed [Federal Reserve] can buy those bonds legitimately because it’s a government-backed asset. You’d have to put restrictions around it; it’d have to be something that would be self-liquidating as opposed to general obligation bonds. You could really do a whole lot of good. I mean, just spending $30-$40 billion on updating the utility grid will save us more than that on our power bills over a few years.

As much as I’m critical of lots of things that China has done, they’ve built an enormous amount of infrastructure, and it clearly shows in their growth rates. We can do that here. For example, we just finished dredging the Mississippi at its mouth so we can now get Panamax container ships up to Memphis. That’s going to be huge. Now they don’t have to stop at the Port of Los Angeles or anywhere else on the west coast. I mean, they can come right into the middle of America and get right off onto trains. That’s going to cut out an enormous amount of costs.

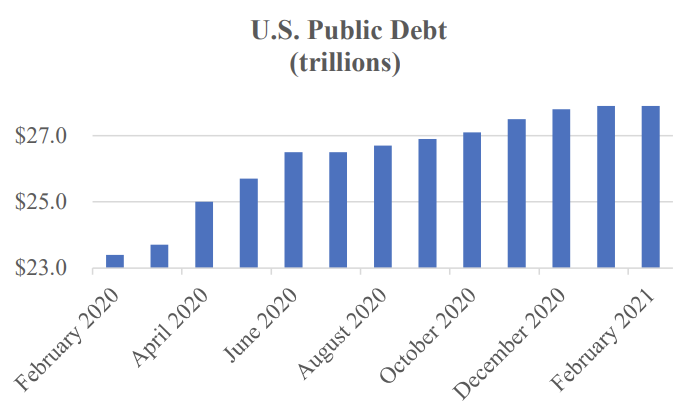

Dirlam: Our feeling – even prior to the Georgia runoffs – was that whatever the political composition of government, there was going to be a lot of spending. The budget deficit was just going to go through the roof. Part of that was seeing how 2020 played out and gauging how markets would tolerate so much deficit spending and with so much monetization of debt by the Fed. In the fourth quarter [2020], the Fed basically bought a third of all Treasury issuance which was about $600 billion. So, we think with this so-called a “blue sweep”, there will be even more spending involved.

They will also likely roll back some of what Trump did. I go back and forth on what will happen with Trump’s tax cuts [the 2017 TCJA]. They certainly don’t have to increase taxes – simply because the markets are so willing to tolerate these levels of deficits and debt monetization. It would be a very politically powerful move to roll back tax cuts, so if one of the administration’s first moves is to do that, I think that’s a pretty strong political statement, especially because there wasn’t a voter mandate in support of increased taxes.

Courtney: I would just highlight that some of these marginally centrist politicians, like West Virginia’s [Senator] John Manchin, become incredibly important now for each specific vote. Ultimately, we don’t think it will be enough to slow the trajectory of increased deficit spending, but to Aaron’s [Dirlam] point, it’s not a mandate for any sweeping action one way or the other. We don’t think the election represented that.

Casey: For a while, I went back and forth on Biden: would he accommodate and advance the progressive policies within his party, or instead be content with just being president – kind of like Clinton – and ultimately not implement any radical changes? His track record and the number of times he’s run for president suggest the latter. But now I fear the former. I think he will actively advance – and not just get pulled into – an extremely progressive, and flat-out dangerous, agenda. I think that conclusion is supported by the ferocity by which he’s issued executive orders, the severity of those executive orders, and the goofiness of doing such things as banning the term “Wuhan virus.” But if the economy deteriorates – and I think that is a strong possibility – maybe the threat of losing mid-term elections will reign him in.

So, what legislation will advance? My fear is that they [the Democratic party] will work to cement their power by enacting long-term, institutional-type changes: make DC [the District of Columbia] and maybe Puerto Rico a state, loosen and expand voting rights, and pack the Supreme Court. Then everything else is fair game. That’s worst-case scenario. Best case is that they content themselves with typical progressive stuff: increase taxes – especially by lowering estate tax exemptions, pass a slew of environmental rules and regulations, establish some sort of universal basic income, etc.

Can they do it? John [Mauldin] is right when he mentions their power is limited by any defection of moderates from their party, but that works both ways. Can we really be confident Republicans won’t defect to their side – especially if something like universal basic income is included in a “necessary” “stimulus” bill? Please put “necessary” and “stimulus” in quotes when you publish this.

WindRock: Whether by executive order or legislation, what do you think the impact will be on energy policy? Whether it’s offshore or fracking regulations or limitations, I imagine it could be good for the price of oil, right?

Courtney: I think it’s more positive for the commodity than it is for commodity-producing equities. We still think it will be broadly positive for the [commodity- producing] equities. The best estimate I’ve seen is that most shale supply will come back on line between $65 and $70 a barrel. There’s obviously been a dramatic reduction in the amount of drilling that’s going on – specifically, in the shale patches. So, we think the market is setting up for a dramatic supply-demand imbalance in the second half of this year. That said, there are some significant developments related to work-from-home culture and what that will do to demand. It’s a little bit more nuanced than “we’re going to return to normal” and “supply is significantly lower than where it was so oil is going to the moon.”

Dirlam: Certainly, a blue sweep paves the way for lots of spending on green initiatives, but I wouldn’t run out and buy any clean energy ETF just because we don’t really know how the government is going to incentivize the green initiative. You could have some companies that just get incredible subsidies that aren’t very profitable and sort of drive down the price of for-profit entities where you’re owning the stock. That to us is an interesting area but we still need to see visibility in an infrastructure bill. We want to see some of the details of how that is going to play out before we would allocate capital to try to take advantage of that opportunity.

WindRock: Do you see any further social unrest in 2021, resembling what we had last year?

Courtney: Without a doubt. I think the burden of proof would be for anyone saying that there won’t be civil unrest. Civil unrest is not uncommon especially in economies where there’s a wide gap between income and wealth levels at the bottom and the top. I think people need to just get comfortable with the fact that this is what the landscape will look like as long as we are trying to fix the economy with monetary policy – which is an extremely blunt instrument and obviously does it in a very unequal way. So, there will be continued social decay and disruption. That’s going to lead to more violence, unfortunately, and just more frustration. I suspect a lot of people are going to get tired of watching their neighbors get rich in the middle of a prolonged recession.

Casey: I think Paul [Courtney] is totally correct. And we have timelines for this already set in stone – namely whenever the verdict comes out for [Derek] Chauvin in the death of George Floyd. But there’s also the possibility of different actors engaging in civil unrest: those against current lockdown measures. If some variant of Covid pops up and new lockdowns are enforced, will parents stand by while kids miss more school? Will loved ones continue to virtually grieve in lieu of attending a funeral? Will people stand by while friends and family are hospitalized with no hope of seeing them and advocating for them in the health care system?

WindRock: Let’s talk about the long-term effects from the lockdowns. What do you guys see as the biggest negative impact, and what could potentially benefit?

Dirlam: The biggest impact is just small businesses going under since they lacked the resources to weather the lockdowns. We had a record number of bankruptcies this past year, and record number of IPO’s. In 2020, you had all of this record corporate and high- yield bond issuance. To me those things say it all. Main Street was left behind, and Wall Street wins again. So, I think unfortunately small businesses are structurally impaired and won’t come back from this.

Mauldin: I agree, the most important economic impact will be for small business. It’s one thing to lock the door and close your small business. But you just can’t take the key, open the door, and go back to business. You’ve got to have inventory, you’ve got to have cash flow, you’ve got to have employees, and you’ve got to have capital. We will have lost thousands upon thousands of small businesses by the time we get through this. That’s a lot of workers, that’s a lot of small businesses, and they just can’t all turn back on when we reach herd immunity.

Commercial real estate is going to get repriced. We’re not going to need as much office space. I think the apartment sector will be less affected except for some urban areas – like New York City – where you have people moving to the suburbs. Just look at the U-Haul numbers. The number of people moving to Arizona, Texas, Florida, Tennessee, etc. is staggering. That’s going to affect housing from the states they’re moving out of, but it’s also going to create housing demand for the states I just mentioned. So, there’s going to be opportunities in real estate in the states that are absorbing the population.

That includes areas where it’s easy to do business or where you want to retire to. As you know, I retired to Puerto Rico, and everywhere I turn around, there’s another opportunity somewhere. We’re actually going to think about how to create a Puerto Rico fund.

Casey: I absolutely agree that small business and commercial real estate – in particular, office space in urban areas with progressive regimes like New York, LA, and Chicago – are the biggest losers. Frankly, I am shocked at how many small businesses have actually reopened, but I fear it’s a swan song for many of them. I personally know of a number of local restaurants, etc. that simply are not paying their rent. At some point, the courts will allow landlords to press their rights.

And let’s not forget that many of the negative effects from the lockdowns have yet to be witnessed: the undiagnosed cancers, the untreated depressions, and increased alcoholism to name but a few. Not to mention the delayed marriages and births, educational setbacks, etc. There’s economic, health, and social carnage everywhere.

WindRock: Given government spending last year, the deficit exploded. It was up $900 billion from 2019 for a total of $2.3 trillion – and that’s with a fiscal year cut off of September 30, 2020. Where do you see debt realistically going in the future? And would you agree that Federal Reserve has no choice but to continue financing them? I mean, the Fed almost doubled its balance sheet in the last year by basically printing over three and a half trillion dollars.

Dirlam: Absolutely. I’ve seen enough headlines or watched enough press conferences of [Chair of the Federal Reserve] Powell and others; and they’re pretty much as outspoken as they can be about begging the government to spend more money because they [the Federal Reserve] can buy the debt. Maybe that’s why interest rates are climbing. But we think they also have to do it because, at their Jackson Hole meeting, they said they’re willing to tolerate higher inflation which will crush the real return of Treasuries. So typical buyers of Treasuries, while still considering it “money good”, will realize they’re not earning anything on them and they’ll have to find something else to meet return needs. I think the Fed is going to have to be the marginal buyer there to keep rates contained. So, it will be more QE [quantitative easing], and it seems like the market is generally okay with that right now.

Mauldin: The national debt will be $40 trillion by 2025, at least, and – because there’s just no impetus for reining in the deficit – we’ll probably be at $50 trillion plus by the end of this decade. Debt is spending brought forward. It has to be repaid. It clearly has an effect on growth in the future. It’s going to slow down growth, and growth is really the only way out of this, but if you slow down growth, you take out one of the major solutions to your debt problem. At some point, I think sometime in the mid to late 2020s, we have to start figuring out what we’re going to do about debt: how we’re going to restructure it and who’s going to pay it. You just can’t make it go away because it’s an asset on someone’s balance sheet. It’s not an easy reckoning.

Casey: I think John is right about where debt is headed. And a few things could easily accelerate that scenario. Most plausible scenario for that to happen: interest rates increase significantly. Higher rates mean larger government [interest] expenses which means deficits increase which means more debt. This thing can easily turn into a death spiral.

And we know what they will do both then and now – print more money. But printing money to suppress interest rates and pay off debt is like basic rocket science; and by that I don’t mean it’s complicated. I mean that printing more money to reduce interest rates – which are also a function of a creditor’s, that being the U.S. government’s, solvency – also increases rates at some level. For rockets, it’s like adding more fuel, in so doing, you’re also adding more weight, which reduces the benefit of adding more fuel. There’s a law of diminishing returns.

Courtney: There will be an overwhelming urge for politicians to spend money that they do have from taxation. Especially with the situation of still high unemployment, very high underemployment, and a significant number of people on some form of government welfare. That’s the only thing I know for sure. Exactly what happens with inflation, exactly what happens with bond yields – well, I think a lot of those types of predictions are really challenging to get right. What we’re trying to focus on is just that overall theme that government spending is going to continue in excess of tax receipts. Which leads policymakers to MMT [Modern Monetary Theory]. MMT is an awful idea whose time has come.

WindRock: How do you envision MMT looking much different from what we’re already doing?

Courtney: We are effectively there now, but I do think just behavior-wise there’s room for it to become more structured and potentially codified in law. That is the key to generating persistent inflation. It needs to become ongoing.

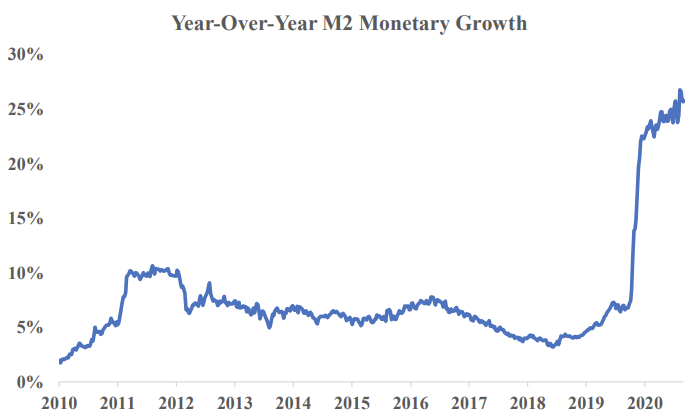

WindRock: Whether or not they go down that path, just given what they already have done, if you look at year-over-year money supply growth over the last 13 months, it’s just off the charts. How concerned are you guys about inflation? And if we get inflation, where do you guys sit on this whole deflation, inflation debate – that is, do we experience deflation first given any economic downturn, or do we jump right to inflation?

Courtney: I don’t care if they’re conservative or liberal, politicians will all do exactly the same thing: spend money they don’t have. Unless Paul Volker [former Federal Reserve chairman] comes back from the grave, there is no way that they do not address any economic hardships, slowdown in the economy, or any stock market decline with anything other than additional spending. As it relates to deflation or inflation, eventually they will outspend some of these deflationary forces. We may get a hot minute of deflation first, which would be the natural order of things if it wasn’t for the central bank, but we know what the response to any deflationary impulse will be: print more money to fund spending. It doesn’t matter how you get there; we end up with higher inflation. And if you look at other measures of inflation, you can argue it’s already here at about 8% to 12%. There’s absolutely no way around it, inflation is going to increase. That doesn’t mean you throw caution to the wind and go all-in on inflation hedges, but I think reminding ourselves of the end game is helpful as we manage risk. Investors should be very judicious with cash and they should raise the hurdle rate for investing in long-term bonds.

Casey: Agreed. As it relates to deflation, I also agree. A “hot minute” is exactly what we got in 2008. The last time we had any significant deflation – as measured in duration and magnitude – in this country was during the Great Depression. The Fed will never let that happen again for three reasons.

First, they are scared to death – incorrectly so – of deflation. They believe, as Milton Friedman incorrectly advocated, that deflation was the cause of the Great Depression. So, they will fight it tooth and nail. Second, deflation hurts debtors since they’re paying back money which is worth more than when they borrowed it. The U.S. government is the largest debtor in the world. It doesn’t want deflation. It cannot afford deflation. Third, with absolutely no link to gold, the Fed is unencumbered in their abilities to act as they wish.

As already mentioned, the Fed has made this very clear. They want long-term inflation at 2%. To “achieve” that, they will let inflation exist above 2% for some time. I still don’t understand why and there’s not justification for it. The Fed is charged with maintaining “price stability”, so I don’t know how that is consistent. In 40 years, the Fed went from fighting inflation to listing it as a policy goal. I don’t know who does the public relations for inflation, but I want to hire that agency.

Dirlam: Today rates are at 0% and the Fed continues to expand the balance sheet with roughly $120 billion in QE per month. Yet, I think they believe that they have the capacity to do more. If you just look at what they sort of did in March and April by buying $125 billion of securities a day. They can step it up as all of the plumbing is in place – especially for them to buy other assets like ETFs, etc.

Courtney: They do think they have more capacity – the Fed’s balance sheet relative to GDP is sitting at about 35%. It’s less than the People’s Bank of China, it’s less than the ECB [European Central Bank], and substantially less than the Bank of Japan.

Casey: It makes you wonder why they’re collecting taxes at all, let’s just print money.

Courtney: That’s exactly the point. That idea is going mainstream. That’s where we’re headed.

WindRock: Do you think central banks will adopt blockchain technology – basically issue their own so- called FedCoin? Do you guys think we’ll get to this point where they actually try to do something like this? What is the motivation – is it because they can inject money more quickly and with greater dispersion.

Dirlam: I think that’s it. Remember, they’re trying to get something that’s higher than a 2% inflation rate for a sustained period of time. They’re not worried about hyperinflation or anything approaching that – it’s not even on their radar. They feel as though they can’t print too much. So, it’s a possibility.

Casey: I’ve always thought they’d be reluctant to institute a so-called FedCoin. If they do so, it destroys their ability to use fractional reserve banking because you can’t have a block in the blockchain in two places at once. If this happens, then I think it evaporates their whole ability to have plausible deniability in being culpable for inflation. Now it seems much more direct, much more correlated. Remember in the 1970’s when they were able to blame the oil crisis, greedy businesses, etc.? A FedCoin destroys that position. But, if they view the benefits as outweighing this negative, they may do it.

WindRock: What are your thoughts on the kind of returns investors should expect going forward? Also, where do you see interest rates headed?

Courtney: Without intervention [by the Fed], interest rates would increase as investors rationally responded to the guaranteed erosion of purchasing power that they will be experiencing in a lot of fixed income securities. And the intervention is just going to increase. At some point, the central bank will just come into the bond markets and essentially nationalize them. When does that happen? We don’t know exactly. I think we’ll probably find out later this year if rates rise on the long end. You’ll probably find out that the Fed is soaking up more and more [Treasury] issuance as is the case in Japan. It might take a year or two but I think that’s where it’s headed.

Dirlam: On the equity side, the S&P500 one-year forward PE [price-to-earnings ratio] is about 23 times, the tech level bubble was 26 times. In a sort of “normal world”, you would look at that valuation along with earnings expectations of like 30%-plus this year and say: “jeez, equity seem to be really overvalued – we should probably be pretty light on that.” But given the dynamics of fiscal policy, we think you need to own equities closer to your allocation targets. There really hasn’t been a material decline in the equity markets when QE has been going on. That old adage of “don’t fight the Fed” we think is appropriate right now even though valuations and prices seem to be way ahead of fundamentals.

Casey: Is the question concerning real returns [meaning after deducting inflation]? You can make a number of arguments why they could be negative for some time. Simply start with mean reversion with or without adding in a potential recession. Perhaps of greater significance for investors is not what returns are for any given asset class, but how correlated they are. Just because something didn’t move in lockstep with something else, and therefore was considered “uncorrelated”, does not mean that will be the situation going forward. I’m primarily talking about stocks and bonds. Bonds saved most investors’ portfolios after the 2008 crisis. I suspect next time they both move together to the downside.

As far as interest rates, the Fed will do everything it can to keep them low. It cannot risk higher rates. They will print to control them until that no longer works. To Paul’s point, they only way they can really try to control this in the long-term is to effectively nationalize those markets by being the sole buyer of Treasuries. If they do that, they will destroy the dollar.

WindRock: It seems like every publication I read is talking about the U.S. dollar declining, having declined, and continuing to decline. Do you guys share that opinion? If so, what are the investment repercussions in your minds?

Courtney: Things that can’t be printed will go up in value. I’m being somewhat facetious but I genuinely mean that. I think the dollar is really hard to call. I do think that twin deficits [the trade and fiscal deficits] are a major headwind.

This has been our working model for a while: the dollar will generally track the combined deficit situation of the U.S. with lag. That’s been the case. But I don’t have a strong conviction that the policy makers in the U.S. will be able to destroy the purchasing power of the U.S. dollar faster than policy makers in Europe or Japan. I am very confident that they will destroy the purchasing power of the dollar. I don’t know if it’s a productive conversation to talk about the relative value of the dollar versus the euro or the yen. But regardless, inflation is here and you need a good reason to hold cash balances. Not to say you should have zero cash balances, but you should also consider other hedges rather than just cash.

WindRock: Where do you guys see the greatest risks and the greatest opportunities in the financial markets right now?

Courtney: The coronavirus has accelerated the disruptive trends that have been in place for at least the last five years. I think some of what’s happening in the blockchain space is incredibly interesting – especially in finance. The DeFi movement has recently gained a lot of traction [Decentralized Finance executes financial transactions without intermediaries.]. We’re super excited about a lot of these disruptive trends, maybe as exciting as anything I’ve seen in my career. I think accessing this space through the private markets is the way to go; look at blockchain venture capital.

Dirlam: The biggest risk is in real estate right now. I think that there’s so much change going on with corporations moving and also allowing flexible, work from home options. The commercial real estate footprint is overall declining. Leases are getting renegotiated. These commercial effects impact residential because they may not be coming in to the office as much. Apartment rent supply in Manhattan is at 19 months which is more than double the ten-year average. Rent prices are down back to levels ten years ago. I really think that’s a big issue.

Casey: I think inflation presents the greatest risk and the greatest opportunity. We know what it does to bonds: it devastates them. We know what it does to equities: it prevents any price appreciation in real terms – stocks basically held their own in the 1970’s. So, how to play any inflation resurrection? There are a number of ways. First, and perhaps most obvious, alternative currencies which are not experiencing the same inflationary pressures. By that I mean precious metals and cryptocurrencies.

Second, any businesses which have costs in an inflationary currency with revenues tied to a stable, or at least a less inflationary, currency profit from the currency valuation discrepancies, and should appreciate dramatically. Primarily, this involves commodity producers. Think of a Russian energy company during a ruble crisis or a Brazilian soybean producer when the real falls.

Finally, assets utilizing extensive financial leverage, especially with long-term, fixed rates, should also perform well. Since inflation helps borrowers to the detriment of lenders, industries with large debt levels such as real estate benefit. Especially true if they have short-term leases with tenants that renew at the new, inflation-adjusted rents. Additionally, as inflation may increase interest rates which deters or limits future borrowing, such industries may experience less future competition, as financing may be cost prohibitive. But keep in mind that not all real estate is created equal. We particularly like build-to-rent residential communities in the Sun Belt.

Regardless, investors should keep two things in mind when seeking out inflation-protection assets. First, the time to buy them is before they’ve been bid up in price. So, for most of these investments, the time is now. Second, because we do not know when or by what magnitude inflation returns, investors should focus on investments which will perform well regardless as to the impact of inflation.

Mauldin: Well, people often call me bearish, and I find myself amused at that. If you looked at my portfolio, you’d find me almost fully invested. I’m not as aggressive as some, I will admit, but my boring portfolio is, in part, made up of large hedge funds, private fixed income, trading strategies – things that I think are going to give me high single digits averaged over four or five years. I also have my speculative part of my portfolio, which I think has the opportunity to give me multiples over time. I’m very optimistic about the future.

But if you’re dependent upon passive index fund investing, you are making a very, very large mistake. If you think passive index funds are going to do in the next 10 years what they’ve done for the past 10, you’re wrong. If you go to the previous 10 years to the aughts [2000-2009], the S&P returned 0% – literally. Then it had 10 years where it’s been lights out, but we’re back to euphoric levels. The last time we were here was 1999, early 2000, and the next decade gave you 0% returns. I don’t know why we should expect something massively different this time. The old line, “past performance is not indicative of future results,” has never been more appropriate than it is today.

Think of it like this, a third of the companies in the Russell 2000 have no income. Now, some of those are good companies and they’re making no money because products are in development or they’re growing rapidly, but some of them are making zero income because that’s just what they do. Investing in these companies just because they’re part of some big ETF with arbitrarily created rules – like market cap size – is a bad idea.

Now, were there opportunities to make money in the aughts? Absolutely. Did active management work?

Absolutely. Absolute returns were the key to having a successful portfolio back then. Dividend portfolios, just plain-old rising dividend portfolios did extremely well.

This is the time to find a good investment advisor, unless you’re one of the 2% of people that are investment junkies and can do that yourself. Otherwise, get a good investment advisor, and make sure that they’re active, look at their portfolios, and look at how they go about structuring things. Don’t let somebody tell you: “Look what it’s done for the last 10 years. Let’s have this passive portfolio of ETFs and mutual funds.” If so, just pick up your notepad and walk away. Go find an investment advisor that understands absolute returns.

This is going to be the year, and I think it’s going to become the decade, of active management.

About WindRock

WindRock Wealth Management is an independent investment management firm founded on the belief that investment success in today’s increasingly uncertain world requires a focus on the macroeconomic “big picture” combined with an entrepreneurial mindset to seize on unique investment opportunities. We serve as the trusted voice to a select group of high-net-worth individuals, family offices, foundations and retirement plans.

The roundtable discussion was moderated by WindRock Wealth Management with the following participants:

John Mauldin

Mauldin Economics

Paul Courtney

SpringTide Partners

Aaron Dirlam

SpringTide Partners

Christopher Casey

WindRock Wealth Management